The Bottom Line In Education, Will the Real Critical Race Theory Please Stand Up?

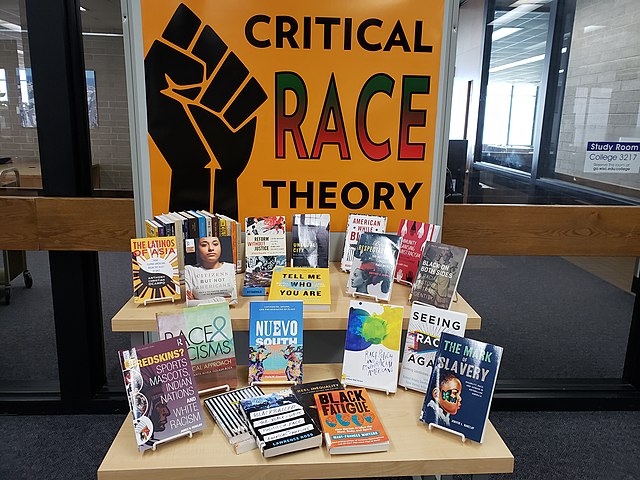

In this article, my goal is to explain the project of Critical Race Theory (CRT) based on source writings of critical race theorists (labeled “crits” by some in the movement). I will attempt to explain the key ideas of the movement and the issues they wish to address fairly and accurately amid an enormous amount of misinformation regarding CRT and K-12 education.

I have argued previously that CRT has no place in K-12 education. But I note there are no critical race theorists driving the push in their literature. The theory does, however, have much to say about what critical race theorists believe to be continued inequities in K-12 education to this day—namely that it has not fulfilled the original promise of the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

The first thing to understand about CRT is its underlying ideology which is, indeed, openly based on the neo-Marxist critical thought of Antonio Gramsci (all societies are divided into two basic groups: hegemonic oppressors and the oppressed) applied to race. CRT, as a movement of legal scholars mostly of color, is an outgrowth of Critical Legal Studies (CLS), a school of critical theory among a collection of white, male, leftist legal scholars of the 1970s who challenged the American legal system, arguing that it served to only legitimize an oppressive social order. As such, critical race theorists agreed with the CLS scholars that traditional American norms of the market system, a pluralistic society, and classical liberalism are found wholly wanting with respect to producing a just society. However, they felt CLS failed to establish a positive program of new norms, particularly with respect to improving conditions for oppressed people of color.

Now it is important to understand that CRT, which was originally a movement of law, has spread out to a variety of spin-off disciplines such as education, voting rights, women’s studies, ethnic studies (e.g., Latino, Asian), and LGBT issues. However, my focus will be on the primary thrust of CRT from a legal perspective and its subsequent relation to education. Thus, we will now delve into two key tenets of CRT with respect to what the movement is for, what it is against, and what it is specifically calling for in terms of remediating past and current social injustices against people of color within the American legal system and the broader culture.

The first key tenet of CRT, which is important to understanding the theory, is its assertion that the law has been historically complicit in upholding white supremacy, which is the social domination and subordination of blacks and other people of color. Though the contemporary legal principle that the law should be “color-blind” and subsequently treat all people equally, it is defective in that it only serves to remedy the most blatant forms of discrimination, such as mortgage redlining and academic hiring practices. Even though the law has worked to suppress explicit forms of white racism, everyday social practices in America continue outside the purview of legal remediation. In other words, critical race theorists believe racism has been and continues to be “pervasive, systemic, and deeply ingrained,” as noted by critical race theorist Richard Delgado

What Bell and other critical race theorists get right is that public school systems in urban areas are failing. While the race-conscious approach to K-12 education advocated by critical race theorists to remediate all that went wrong after Brown is problematic… we would certainly agree that urban public school failures are in large part due to their massive and inefficient bureaucracies, a one-size-fits-all approach to education with little to no innovation, and teachers’ unions that advocate for teachers at the expense of students and parents.

Critical race theorists believe common, liberal ideals such as “color-blindness,” “formal legal equality,” and “integrationism” are simply rhetorical tools of power incorporated in American academic and workplace institutions, supported by Supreme Court jurisprudence that has accepted and confirmed an oppressive racial regime in the decades after the civil rights era. They cite court cases where the Supreme Court has eschewed race-conscious policies in the areas of minority set-asides, de facto racial segregation, and voting rights. Interestingly, critical race theorists admit these decisions are consistent with neutral, liberal racial principles. However, critical theory rejects, as noted, the classic liberal visions of racial justice, seeing them as an attack on government efforts to address continuing societal racial discrimination.

The second key tenet of CRT, sometimes called “interest convergence,” is a notion advanced by critical race theorist Derrick Bell, who argues that in achieving racial equality, the interests of blacks will only be accommodated when they converge with the interests of whites. In other words, a judicial remedy for racial equality will not be authorized if that remedy in any way threatens the superior social status of middle- and upper-class whites. Thus, any racial remedy as an outward manifestation must, in the subconscious of the judiciary, advance or at least cause no important societal harm to this group. Perhaps shocking to some, Bell uses Brown as a notable legal example whose result was more in the self-interest of elite whites than the court’s desire to help blacks. It ameliorated criticism from communist countries during the Cold War, and reassured blacks who recognized that the Soviet Union, whom they fought against in World War II, acknowledged their full human dignity.

As to the first tenet, it is an unfortunate fact that in the past, laws were sometimes explicitly written to discriminate against black and other students of color, and even neutral laws were often intentionally and purposefully abused. However, those discriminatory laws have largely either been struck down by the courts or replaced with non-discriminatory laws by Congress and state legislatures. While it is true that color-blind, neutral liberal ideology has its limitations, as it cannot reach into the hearts and minds of human beings in their everyday social practices to completely eliminate discrimination, the argument that racism continues to be systemic and supported by law is unconvincing.

I also find the notion of interest convergence tenuous at best in the 21st century. With respect to education, the Brown decision did indeed yield benefits for white Americans. However, the primary benefactors were blacks in terms of its striking down longstanding, intentionally racist and discriminatory school policies.

What I think Bell gets correct, however, is that the focus after Brown was wrongly on integration, which had highly mixed results, often ending in violence and “white flight” over the course of the next two decades. Alas, many schools are just as segregated now as they were prior to 1954. Bell argues that the focus should have been on providing black children with equal and adequate school resources, wholly apart from whether the school was integrated or non-integrated.

What Bell and other critical race theorists also get right is that public school systems in urban areas are failing. While the race-conscious approach to K-12 education advocated by critical race theorists to remediate all that went wrong after Brown is problematic, there may be common ground here. Namely, we would certainly agree that urban public school failures are in large part due to their massive and inefficient bureaucracies, a one-size-fits-all approach to education with little to no innovation, and teachers’ unions that advocate for teachers at the expense of students and parents.

Ironically, those pushing for the “teaching” of CRT in K-12 education, which is hardly a viable educational subject, are among those whom critical race theorists argue are largely responsible for the lack of educational equity and attainment in urban public school systems today.