Book Excerpt: How Tech and Government Can Spin the Flywheels of Equitable Prosperity Together

Originally published at GeekWire“Flywheels: How Cities are Creating Their Own Futures,” is a new book by Tom Alberg, former Amazon board member, and managing director of Madrona Venture Group in Seattle, published by Columbia University Press. Excerpt reprinted with permission.

The most dynamic way to think about the economic flywheels of Seattle and Silicon Valley is that creative people combined with innovation to beget startups.

Those small startups — including not only Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Facebook but also less famous ones — grew into successful companies that attracted talented people who generated new wealth. Many of those creative types, in turn, came up with innovations and launched new startups such as Netflix, Instagram, Redfin, and Rover — an ever-expanding constellation of companies.

The flywheels kept spinning, faster and faster, such that both regions are now home to hundreds of technology startups — most with names you’ve never heard of — adding millions of dollars to the tax base, alongside their Amazons and Googles.

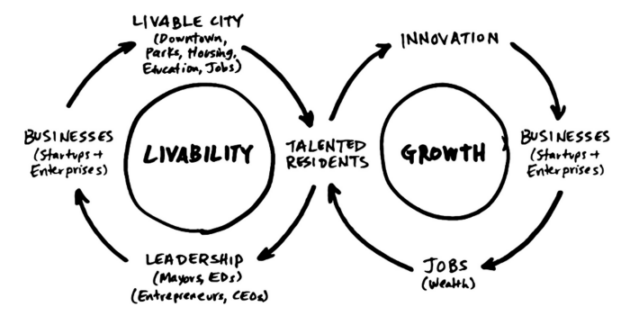

Even though the economic flywheel has provided jobs and created wealth for spending and investment in leading tech cities, it has not solved the social challenges of homelessness, inadequate education, public safety, and transportation. These need addressing by the livability flywheel, targeting social ills and using social innovation as well as economic drivers.

The livability flywheel depends on leadership from elected officials, corporate and nonprofit executives, and the community. They can lead the restoration of their downtowns with parks, housing, arts, schools, and jobs. This will attract talented people who create and staff businesses and provide civic leadership. All of which strengthens the livability flywheel.

The two flywheels have several common elements. Both depend on talent that produces innovation and leadership. Both depend on a dynamic, growing business community that produces wealth that finances livable cities and universities and schools that produce talent. And both depend on a livable city that attracts talent and businesses.

Cities need both flywheels to thrive. Although Seattle and San Francisco were highly successful in using economic flywheels to develop their modern tech economies, they are now struggling to reverse the slowing of their livability flywheels.

Tech cities such as Seattle and San Francisco have attracted wonderful talent from across the globe and have created enormous economic benefits but they are endangering themselves as social conditions worsen and conflicts between the government and business increase.

So, it bears asking: Why can’t cities and businesses that nurtured world-changing innovations work together to fix their social ills?

Finding common understanding

An important step in bridging the divide between the business and political communities is reaching a common understanding of the roles of government and business in solving urban problems. It has been long expected that the role of businesses was to produce jobs and pay their fair share of taxes to support the city, which was responsible for public safety, public schools, a safety net, zoning, public amenities such as parks, and transportation planning. Of course, it was never this tidy. Businesses bridled at what they thought were unfair taxes and often opposed government regulations and planning. Governments too often have failed in their tasks.

In years past, we welcomed the prospect of Seattle’s businesses leading the search for civic solutions. In 1968, a coalition of corporate leaders and engaged citizens launched successful voter initiatives to build new parks and pay for the cleanup of Lake Washington. In 1971, citizens launched an initiative that defeated a disastrous city council plan for demolishing Seattle’s famed and historic Pike Place Public Market and replacing it with a complex of apartments, office buildings, hockey arena, and four-thousand car parking garage. Today the public market is bustling, serving tourists and locals with dozens of vendors of produce, fish, cheese, meats, and flowers.

In the early 2000s, the Gates Foundation funded a $10 million transportation study by the Cascadia Center for Regional Development of the Discovery Institute offering solutions for replacing Seattle’s aging Alaskan Way Viaduct, an elevated highway along the waterfront. Everyone had recognized for years that the viaduct was an eyesore walling off the waterfront from downtown and an earthquake hazard; no one could agree on a fix.

Political leaders dithered and waved off the study’s recommendation to rebuild the highway with a tunnel beneath our city streets. Flat-out crazy, local leaders and transportation experts said. But after the Cascadia Center organized conferences to highlight examples of tunnels in other parts of the world, flying in experts to answer questions, then-Governor Gregoire endorsed their recommendation. The viaduct was demolished, and a two-mile tunnel funnels drivers below Seattle’s downtown on a four-lane underground road that has opened up the waterfront to downtown residents, office workers, and tourists.

Another example: In the 1990s, Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen purchased a swath of underdeveloped downtown real estate, intending to create Seattle’s version of Central Park. At the time, this was a blighted area of warehouses, abandoned buildings and parking lots. But when voters twice rejected the necessary bond issues, Allen changed course, developed the property, and attracted Amazon to create an urban campus. Now fifty thousand workers have energized the neighborhood of restaurants, shops, and apartments.

So, we’ve done it before, leveraged private financial assets and leadership to design innovative solutions for the public good. Are our current problems of homelessness, schools, transportation, and housing so different from cleaning up pollution, redeveloping blighted streets, or solving the riddle of the viaduct? I don’t think so. A hopeful sign is that technology companies and individuals are increasingly using their money, leadership, and technology to help solve civic problems, including homelessness, worker housing, PreK–12 education, transportation, and the environment. But it is a big, complicated agenda that needs increased support by government, foundations, and private businesses and leaders.

Civic leadership is paramount

Viable solutions will not arise from a watered-down consensus. What we need is leadership—ideally from a strong, politically astute mayor who can articulate the urgency of a problem, rally sufficient support, and organize governmental and private sector resources to execute solutions. Ideally, he or she would identify the community’s most important problems, analyze the root causes, and implement innovative solutions.

But we can’t always count on leadership from an inspired mayor. As an alternative, we can encourage and support individual and business initiatives. I believe the most effective approach is to create separate coalitions of businesses, nonprofits, and citizens focusing on specific problems as we have in the past with our history of meeting challenges like polluted water and urban blight. I’ll be blunt: groups encompassing diverse and contradictory opinions have difficulty pulling on one rope in the same direction to get anything done. But single-purpose coalitions can gather people who are passionate and knowledgeable about particular problems, willing to devise new solutions, able to focus their fundraising, and willing to endure opposition. Empowering such coalitions to make timely decisions and take decisive action is much more likely to achieve positive results than time.

Although many projects can be driven by businesses with minimal help from the government, the best outcomes will come from businesses and governments working together. Leadership for such coalitions can often come from the business world, but it can equally come from passionate nonprofit leaders and citizens.

I hope we are past the issue of whether businesses should play activist supporting and leadership roles. Legal scholars love to debate the theoretical role of corporations in civic life, pondering whether their raison d’etre is solely profit, or whether their fortunes rise and fall with those of their home communities and other constituencies. The national Business Roundtable, composed of 181 CEOs, recently redefined the purpose of businesses as no longer only for the benefit of shareholders but also for “the benefit of all stakeholders — customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders.”

There are business critics of these broader purposes, but it seems obvious that modern businesses cannot be successful unless they treat their customers and employees well nor attract and retain creative thinkers in cities with mediocre schools, poor transportation, and rampant homelessness. If recent history is any guide, it is unlikely that these problems will be remedied unless businesses actively participate in the solutions. The way I see it, cities need the risk-taking innovation and creative brainpower of businesses that are central to our tech economy.

COVID-19 response offers an example

The response of businesses to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how effective and important business involvement can be in helping solve major civic problems, particularly in supplementing and working together with government efforts. Critical to the development of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments in record time was the work of companies like Pfizer, Moderna, BionTech, Regeneron, and Eli Lilly in creating, testing, and manufacturing — all based on years of research at federal, university, nonprofit, and business labs. In response, the Federal Drug Administration showed that it could speed up its approval process while protecting public safety.

Although the federal government and most states faltered in their initial rollouts of testing and vaccines to sites for giving shots, they were essential to providing testing and vaccines on a large scale. Businesses stepped up and joined hospitals to increase the number of vaccine sites. For example, Amazon and Microsoft used their considerable logistical skills, software skills, and scale to quickly set up vaccination sites on their properties to vaccinate thousands of the general public per day.

Though Seattle has a strong nonprofit community with dedicated leaders working on homelessness and public schools, their efforts need greater financial support from local businesses and foundations. More businesses need to follow the examples of Microsoft and Amazon. Many of our largest foundations, including the world’s largest, the Gates Foundation, have a global focus. Even though they also are important contributors to local programs, I often think they should play an even bigger role locally with larger financial contributions considering their resources and that this is their home community from where they derived their original wealth and where their employees live and work.

Is Seattle’s dream dead? Does our inability to solve our city’s problems threaten our ability to be able to continue to attract the creative people critical to our future? Or can Seattle’s economic success be harnessed to support civic progress?

Can we have cities that are livable and welcoming for all, where people are not living — and dying — on our streets and where students from every economic bracket can rise to take advantage of the enormous opportunities that exist? Yes. But to do so, we need to make some changes.

Unless technology companies and cities find new ways to work together, the continued success of both is under threat. And they must smartly apply technology to help solve the problems. Just as businesses are using AI, cities should harness the ability of AI to analyze problems and propose and manage complex solutions. Cities should be leaders in making use of innovations in artificial intelligence, medicine, communications, and transportation technologies that are revolutionizing our lives.

Keeping our flywheels spinning is not a given. This moment is important. Business and political leaders must put aside their traditional antipathies. Politicians must dampen their antibusiness rhetoric, and business players must, as Jeff Bezos has stated, expect to be “scrutinized” by the press and government.

Let’s use Seattle’s extraordinary prosperity and growing creative classes in Seattle and San Francisco to attack the problems threatening to undermine our meteoric success. Let’s institute a change in city government, opening its traditional processes to problem-solvers from outside.

Then let’s evaluate the results dispassionately and act decisively. I don’t believe any single entity — local governments, Amazon, the Gates Foundation, or anyone else — can solve Seattle’s problems by themselves. But our old systems are not doing the job. And our culture of innovators seems an obvious, untapped source of new answers. We need this new generation of younger citizen, business, and government leaders who are not afraid of trying new solutions. We need to take advantage of our culture of innovation.

If we can’t make tech cities great places to live as well as to work, we threaten the economic and livability flywheels built over the last generation.