Six Solutions for Seattle – Global City or Just Another Town?

The Time is Right to Honestly Assess the Region's FutureMETROPOLITAN Seattle — from Everett to Tacoma and from Puget Sound to the Cascade foothills — in the past decade has become a true international “Citistate,” to use the term coined by syndicated columnist Neal R. Peirce.

Like many of the world’s great metropolises, the region’s economy now almost has a life of its own, closely connected to the growing global marketplace.

This development affects nearly all of us — in terms of jobs, education, government and quality of life. More than ever before and more than any other community in the country, central Puget Sound’s prosperity is now tied to international trade. While most attention is paid to the largest players, Boeing and Microsoft, our area also is home to countless other companies with international markets, whether in high technology, financial and legal services, forest products, tourism, health care, food products or entertainment.

These are the businesses that have provided the jobs — and growing tax base — of the last decade. Without them our economic condition and state budget problems would be much worse.

But the current period of economic challenge — marked by a host of impending new state and federal government taxes and regulations, and deep concerns about the quality of education — has raised new questions:

Can metropolitan Seattle continue to compete internationally? Can new international businesses get a good start here? Will we remain attractive to foreign investment? What will happen to government revenue, private-sector jobs, the environment, education and our children’s future if we fail to lay a sounder foundation for participating in the increasingly global economy?

After Fortune magazine last November rated Seattle the “best city in the U.S. for global business,” a follow-up survey of local leaders found many skeptical about this region’s continued competitiveness. They expressed concern about increasing tax burdens, transportation problems and permit delays. Today, those concerns are surely even stronger than they were six months ago.

A Discovery Institute project, “International Seattle: Creating a Globally Competitive Community,” is aimed at helping the region define a new strategy for increasing its international competitiveness. With the help of a 24-member advisory board and a host of volunteers, we have conducted interviews throughout the region and studied a dozen other cities’ international programs.

Our preliminary analysis and recommendations — in the form of a 65-page draft report — will be presented at a public conference Thursday. The comments and ideas we receive there will be reviewed for our final report and action plan that will be offered to the region’s elected and private-sector leaders.

We found that internationalism offers opportunities, but it also issues a challenge to local and regional leadership: either we adapt to the increasingly global standards of competition or our hard-won economic and social gains can be lost.

Among the preliminary recommendations:

Leadership

Metropolitan Seattle needs a unified structure for addressing the international concerns that the many sectors of our community have in common. One organization, drawing on the collaborative contributions of all affected levels of government and private groups, should be designated to act as a kind of combined trade and foreign office. To set this recommendation in motion, an “International Summit” should be convened by a coalition of public- and private-sector leaders.

It was a breakthrough in 1990 when community-wide response to international concerns led to the creation of the Trade Development Alliance of Greater Seattle. The “TDA” pulled together resources from the city of Seattle, King County, the Port of Seattle, the Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce and organized labor, with a stated goal of making this region “one of North America’s premier international gateways and commercial centers.”

What is needed now is an organization with:

- a wider geographic range than is present under the TDA, embracing the three- or four-county area that is the true metropolitan region;

- a wider variety of participants, including higher education, K-12 schools, and private nonprofit groups;

- a wider mandate, extending from trade to the overall strategy for a globally competitive community.

The best option for creating such an organization would be to adapt the present Trade Development Alliance to this larger, more inclusive mission. That cannot happen easily, of course. Any one of the three forms of expansion (geography, participation and mandate) will require extensive deliberation and negotiation. It may be necessary to do this particular job in steps.

Cascadia

Metropolitan Seattle’s strategy for global competitiveness should embrace a closer alliance with our northern neighbor, Vancouver, B.C., as part of an overall advancement of the bi-national region of “Cascadia.”

The increasing cross-border cooperation in the Pacific Northwest and Canada is one of the most promising developments in international regionalism in decades. The Seattle-Vancouver, B.C., tie is crucial, and one of the most natural international metropolitan relationships in the world today. In the immediate future, for example, we should be launching “Cascadia” trade and tourism missions that combine some of our bi-national region’s overseas sales efforts.

However, the Seattle-Vancouver, B.C., connection also must open up to include Portland, as part of the “Cascadia Corridor,” a line of interests along the Interstate 5 freeway. And then, still wider cooperation is needed in the whole Northwestern U.S. and Western Canada, the land that many have begun to call “Cascadia.”

Much progress has been made in recent years. The Pacific Northwest Economic Partnership, primarily an executive branch initiative, has been working for mutual economic benefit for several years. So has the Pacific Northwest Economic Region, led by legislative officials in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Alaska, British Columbia and Alberta.

The Pacific Corridor Enterprise Council (PACE) is a promising private-sector initiative. And more recently, the effort to create a Cascadia Corridor Commission has made great strides in a short time, focusing its efforts along the I-5 corridor.

Ports

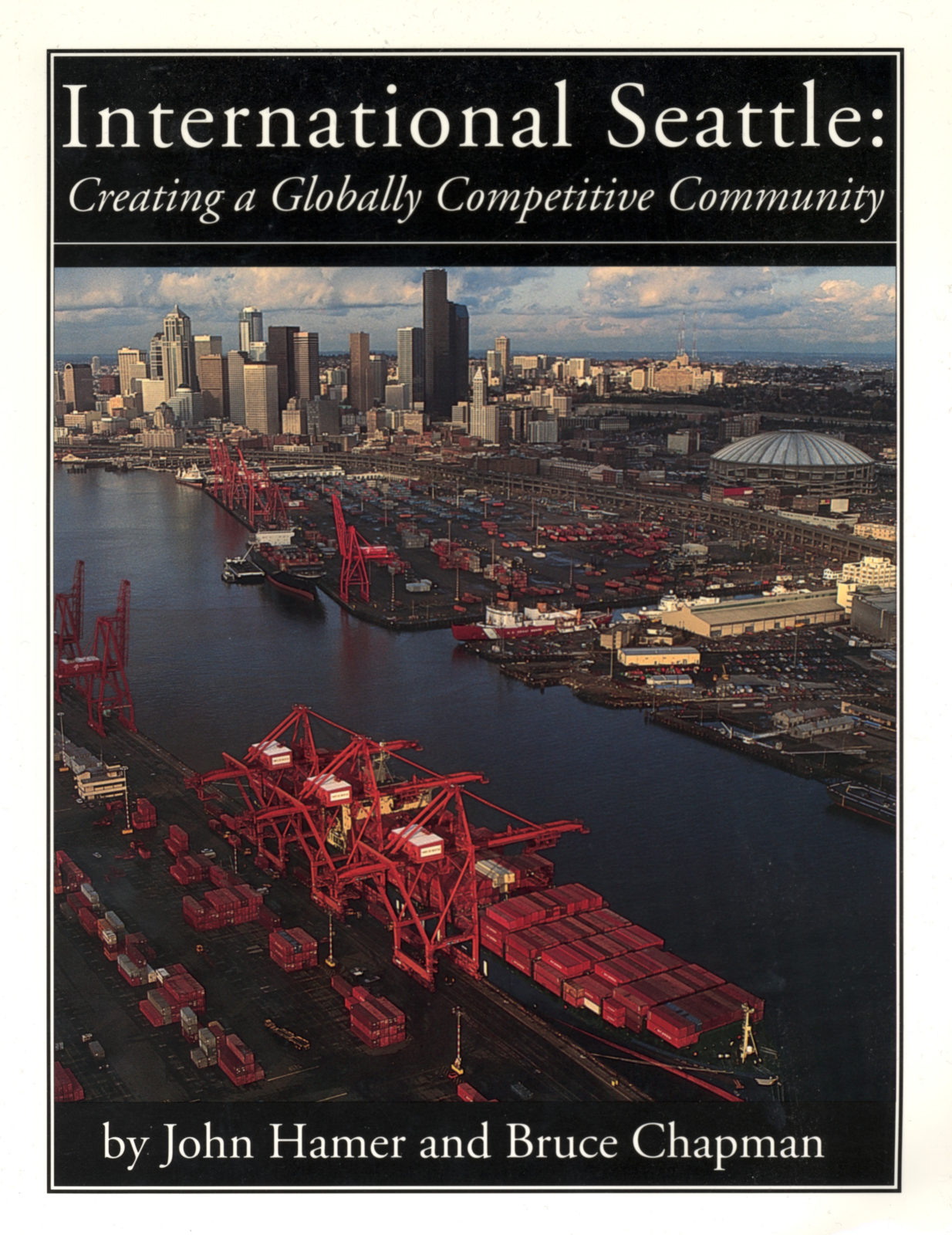

The Ports of Seattle and Tacoma should work as equals toward a strategic alliance to promote greater efficiency in marketing the region internationally and making optimum use of each port’s assets. This alliance eventually could lead to the formation of a combined Seattle-Tacoma Port Authority.

In the increasingly competitive global marketplace, it is vital to have more cooperation among Puget Sound area ports. There is opposition to this concept, especially in Tacoma, but the case for cooperation is so strong that we believe the subject should remain open to continuing dialogue. Perhaps the relationship can best be built gradually.

There have been encouraging signs of cooperation recently. Both the Ports of Seattle and Tacoma are helping finance the state/ports promotion office in Paris. But Tacoma, which has been more competitive with Seattle in the past and will continue to be so because of its large land holdings near the waterfront, has been reluctant to formalize any relationship and is suspicious of Seattle’s motives.

An inter-local agreement to form a strategic alliance would be a good place to start. In 1991, a combined Seattle-Tacoma Port Authority would have been the second-largest container facility in the United States, behind only Los Angeles-Long Beach and ahead of New York-New Jersey, both good models of combined port authorities.

Tourism

International tourism should be given a higher priority within existing tourism promotion efforts. Meanwhile, a consortium of tourism experts should prepare a factual justification for state and local governments to increase this region’s relatively small current investment in tourism promotion.

International tourism and tourism generally represent an under-utilized source for tax-revenue growth and the creation of badly needed low- and medium-skill-level jobs. Nationally, international tourism is growing by about 15 percent annually, while domestic tourism is growing by only about 6 percent a year. However, this state is now 49th out of 50 states in per capita spending on tourism promotion, and last among seven major Western states in total spending. And the Legislature has cut the budget for tourism promotion by 35 percent over the past five years, despite the fact that tourism is the state’s fourth-largest industry and has the potential to become much larger in the future. The state is missing a chance to strengthen our economy – and the state’s revenue base.

One tourist sector that has long been underdeveloped in metropolitan Seattle is the cruise-ship industry. Because of the federal Passenger Service Act of 1886, which prohibits foreign-flag passenger ships from one-way service between U.S. ports, most cruise ships (which are nearly all foreign-flagged) do not stop in Seattle. Efforts to amend the law have been blocked in Congress by labor unions and domestic cargo-ship interests who fear any changes might detrimentally affect the U.S. merchant fleet.

Thus, because of a century-plus-old law, Seattle is prevented from being a port of embarkation for cruise ships traveling to Alaska. As a result, this area loses millions of dollars and thousands of jobs to Vancouver, B.C., which has become a center of the lucrative Alaska cruise-ship industry.

The Port of Seattle is building a new cruise-ship terminal as part of its waterfront redevelopment project. Some Vancouver officials, indeed, believe that if Seattle is able to attract more cruise ships, the overall growth in traffic will ultimately help both cities.

K-12 education

The metropolitan region’s school leaders, both public and private, should realize that their students are competing as much with students from other countries as from other U.S. cities. Therefore, by the year 2000, schools should increase by 50 percent the number of students who take foreign languages, and the average number of years they study each language.

Improving foreign-language training in public schools must become a much higher priority if our area is to compete successfully with communities in Europe and Asia. Although Washington state is No. 1 in the U.S. in per capita trade, it was No. 25 in the percentage of high-school students who study foreign languages, according to a 1990 survey by the American Council on Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Currently, only about 40 percent of this state’s high-school students study a foreign language, and then for an average of only two years — not enough to gain fluency. The goal should be to increase the percentage to at least 60 percent, and to raise the average number of years studied to at least three. At least 20 percent of all students should graduate with genuine fluency in a foreign language, not just a rudimentary knowledge. To accomplish this, it will be necessary to start language education in the elementary schools. It should be possible for students to take up to 12 years of major languages such as Japanese, German, French, Spanish, Russian and Chinese. In addition, a special study commission should be formed to re-examine the idea of establishing a new International High School somewhere in the metropolitan region.

Higher education

The University of Washington, and other regional colleges and universities, both public and private, should give a higher priority to their international activities. The UW should appoint a Vice Provost for International Affairs to coordinate its international activities, and should put as much emphasis on international affairs and high technology as it does on forestry and fisheries.

The UW and some of the region’s other colleges and universities have some excellent international programs, but just as the U.S. private sector has become more globally oriented in recent years, American higher education must do the same.

Many additional recommendations on how to make this a more globally competitive community are offered in Discovery Institute’s report, ranging from airport expansion, attracting more international conferences and foreign consulates, better promotion of the arts and museums, and improved telecommunications systems. Overall, we believe that a comprehensive strategy of international competitiveness is the best course for this metropolitan region to pursue in the next decade and beyond. It is not an exclusive strategy. In fact, it is the one that will work best with others. It fits not only our regional emphasis on high technology, but also accommodates well to prudent natural-resource management, environmental protection, high-quality urban design and thoughtful social policies.

We will succeed best if we fly with the global wind currents rather than against them.

John Hamer is a senior fellow of Discovery Institute, a Seattle-based public policy organization. Bruce Chapman, a former U.S. ambassador, is the institute’s president.

———————- CONFERENCE ON SEATTLE ———————-

“International Seattle: Creating a Globally Competitive Community” is a Discovery Institute conference planned in cooperation with the Trade Development Alliance of Greater Seattle and the World Affairs Council. The conference will be Thursday from 8 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. at the Four Seasons Olympic Hotel in Seattle. Call 287-3144 to register or to order a copy of the report.

Speakers include: Neal R. Peirce, syndicated columnist who wrote the “Peirce Report” for The Times and is author of a new book, “Citistates: How urban America can prosper in a competitive world”; Panayotis Soldatos, director of the Institute for the Study of International Cities in Montreal; Mayor Manfred Rommel of Stuttgart, Germany, (via teleconference); and Craig O. McCaw, chairman and CEO of McCaw Cellular Communications Inc.

Other speakers include: Douglas P. Beighle, senior vice president of The Boeing Co.; Mayor Norm Rice, Sen. Slade Gorton, Gov. Mike Lowry, Secretary of State Ralph Munro; University of Washington Vice Provost Carol Eastman; civic leader and attorney Jim Ellis; Helen Marieskind, president of Sime Health Limited; Paul Schell, Port of Seattle commissioner; Susan Mochizuki, executive director of the Japan America Society; and John R. Miller, former U.S. congressman.