We Need to Bring Back Real Debates in America

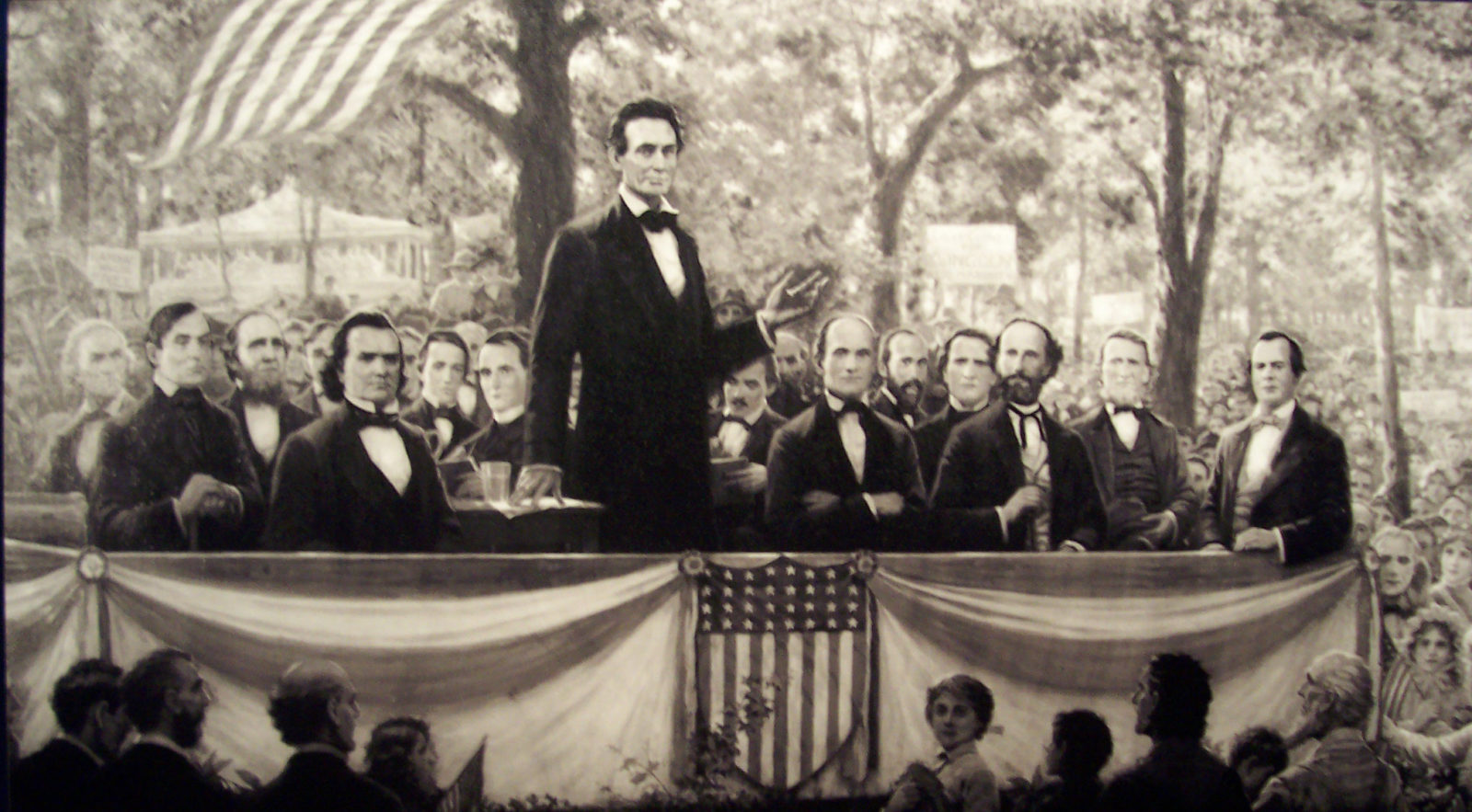

Crossposted at CNS NewsThe televised Democratic presidential sound byte pageants will not be true debates by any realistic standard. They are reminiscent of the 2016 Republican primaries that started with 16 candidates preening on a platform and enduring “gotcha” questions by reporters/moderators trying to get themselves into the news story. Until the nominee field narrows, these shows are almost a parody of real debates in the Lincoln-Douglas or Oxford Union manner.

That’s too bad. We need to bring back real debates in America, and not just among candidates. Name the issue (climate change, foreign interference in our elections, abortion, immigration, tariffs, privacy online, the future of artificial intelligence, the meaning of “free speech,” whatever): Americans are badly divided. Since media and politicians often operate in inward-looking communities, they tend to ignore or distort views that differ from their own. In this environment, mere calls for greater civility don’t work. What can work is facing issues straight on and together.

A proper debate is a robust but orderly confrontation of views, where set rules assure that both sides are displayed in such a fashion that people can judge for themselves which seems most correct. Conservatives, who enjoy relatively little access to academia, newspapers and television, and who therefore lack many chances to confront their adversaries on common ground, should take a special interest in debates.

Walter Lippmann, one of the 20th century’s leading essayists, noted that “the modern media of mass communications do not lend themselves easily to a confrontation of opinions … Rarely, and on very few public issues, does the mass audience have the benefit of the process by which truth is sifted from error — the dialectic of debate in which there is immediate challenge, reply, cross-examination and rebuttal … . Yet when genuine debate is lacking, freedom of speech does not work as it is meant to work. It has lost the principle which regulates it and justifies it …”

Lippmann was a liberal, but of a kind that is becoming rare. Cultural leaders on the left now routinely seek to deny opponents a hearing, speaking past them and looking for vindication in the courts. Most of the commanding heights of communications and organizational power are largely in the hands of people who consider conservative views illegitimate. The same is true of most foundations and big businesses.

Meanwhile, campaign consultants in both parties advise candidates that it is more important to find your voters and get them to the polls than to win over the opposition or even worry about the undecided.

But, it is a paradox of democracy that real debates are often the most reliable way to help public opinion mature in a reasoned manner. In a debate, each side is heard in its own voice, and not just interpreted by some observer.

When sponsoring or attending a debate, the community expresses its desire to hear out competing arguments, and it will pressure both camps to take part. That makes it hard for people trying to ignore their opposition and to duck a contest of ideas. At a debate, furthermore, the audience tends to turn against claques or extremists that seek to prevent the debate from proceeding.

On college campuses in recent years controversial speakers on the right have been shouted down or even physically attacked. College conservatives therefore should be especially interested in promoting debates as occasions when at least some of their colleagues — those on the sane left — would join them in resisting the disrupters.

It is important, however, for them to understand what is real debate, and what is not. Whole generations have grown up without much experience with the tradition and many public figures pay debate lip-service, but provide something very different. A panel of experts being interviewed is not a real debate. Talking heads interrupting each other and being interrupted by a commentator are not debates. Theater? Sure. Debate, no.

Even in a final nation election campaign with only two or three candidates on stage, few debates today have the focus, say, of the famous 1858 Lincoln-Douglas contest — where many Americans for the first time heard a sustained argument on slavery. Back then, people with only a grade school education stood outside to listen — politely and for hours — to what today would be considered a sophisticated clash of views. Think of them when someone tells you that Americans today will not take serious debates seriously.

It would help, of course, to have more people capable of debating in public, as well as attending debates. There are still national organizations, such as Junior State of America and the National Speech and Debate Association, that sponsor debates among high school students. A number of universities are sponsoring debate “camps” this summer.

However, the debate movement among youth may be stagnating as the teaching of civics has yielded to classes in “Action Democracy” where students get credit for participating in protest demonstrations or lobbying the state legislature on behalf of some issue fashionable at school.

Adult debates are even rarer. One exception is New York’s Intelligence Squared U.S., a non-partisan sponsor of periodic public debates, each livestreamed and made available online. Another is Pro/Con.org, located in Santa Monica, CA. Pro/Con has staged Debates at the Pier on Santa Monica’s waterfront, raising such topics as “Abolish ICE?” and “Marijuana Legalization in California: Is it Working?” Well-versed debaters are invited on each side. With a budget of under a million dollars a year, Pro/Con.org is, perhaps most importantly, a rich online resource for thousands of students, researchers and journalists on a wide array of debatable issues.

One of the most frequent changes that happen in a formal debate, says the recent director of Pro/Con, Kamy Akhavn, is the development of respect by audience members for an intelligent opinion that is different from their own. That by itself is a precious accomplishment.

At the beginning of a Pro/Con or Intelligence Squared debate (as in Oxford style debates), audience members are tallied for their initial positions. After the debate they are tallied. Often, there has been a shift.

For people who believe that a fair hearing will help their cause — and that today describes most conservatives — debates offer an underemployed option.