What do Modern Textbooks Really Say about Haeckel’s Embryos?

Many Darwinists are currently making much noise on their blogs and at movie screenings, trying to rewrite history by claiming that Haeckel’s embryo drawings were never used in modern textbooks. In a contradictory claim, some then concede that modern textbooks have used the drawings but argue that Haeckel’s work was only cited to provide some historical context to evolutionary theory—they assert that Haeckel’s fraudulent drawings have not been used to promote evolution in modern textbooks. They are wrong on both counts.

To avoid confusion, let me point out that we are not claiming that Haeckel’s embryo drawings and recapitulation theory are the bedrock of evolutionary biology in 2007. Nor are we arguing that every textbook that has used Haeckel’s fraudulent drawings (or some near-identical colorized version) therefore promoted the idea that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” As Jonathan Wells points out in his recent article, The Cracked Haeckel Approach to Evolutionary Reasoning, “Many modern biology textbooks inform students that Haeckel’s dictum, ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,’ has been discredited, but the same textbooks often use Haeckel’s drawings (or modern versions of them) to persuade students that human embryos provide clues to our evolutionary history and evidence for Darwin’s theory.” Therefore, what we are claiming is that various modern textbooks have used Haeckel’s embryo drawings in precisely the manner that Darwinists now deny:

- (1) They show embryo drawings that are essentially recapitulations of Haeckel’s fraudulent drawings — drawings that downplay and misrepresent the actual differences between early stages of vertebrate embryos;

- (2) They have used these drawings as evidence for evolution — in the present day — and not simply to provide some kind of historical context for evolutionary thought;

- (3) Even if the textbooks do not completely endorse Haeckel’s false “recapitulation” theory, they have used their Haeckel-based drawings to overstate the actual similarities between early embryos, which is the key misrepresentation made by Haeckel. They then cite these overstated similarities as still-valid evidence for common ancestry.

Some Darwinists continue to deny that there has been any misuse of Haeckel in recent times. If that is the case, why did Stephen Jay Gould attack how textbooks use Haeckel in 2000? Gould wrote: “We should… not be surprised that Haeckel’s drawings entered nineteenth-century textbooks. But we do, I think, have the right to be both astonished and ashamed by the century of mindless recycling that has led to the persistence of these drawings in a large number, if not a majority, of modern textbooks!” (emphasis added) Similarly, in 1997, the leading embryologist Michael K. Richardson lamented in the journal Anatomy and Embyology that “Another point to emerge from this study is the considerable inaccuracy of Haeckel’s famous figures. These drawings are still widely reproduced in textbooks and review articles, and continue to exert a significant influence on the development of ideas in this field.” (emphases added)

Below are listed a number of such modern textbooks which have used Haeckel’s embryo drawings in the fashion stated above. The list includes an analysis of each textbook, with documenting graphics:

- I. Peter H Raven & George B Johnson, Biology (5th ed, McGraw Hill, 1999)*

- II. Peter H Raven & George B Johnson, Biology (6th ed, McGraw Hill, 2002)*

- III. Textbook III. Douglas J. Futuyma, Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed, Sinauer, 1998)

- IV. Cecie Starr and Ralph Taggart, Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (8th ed, Wadsworth, 1998)

- V. Joseph Raver, Biology: Patterns and Processes of Life (J.M.Lebel, 2004, draft version presented to the Texas State Board of Education for approval in 2003)

- VI. Cecie Starr and Ralph Taggart, Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (Wadsworth, 2004, draft version presented to the Texas State Board of Education in 2003)

- VII. William D. Schraer and Herbert J. Stoltze, Biology: The Study of Life (7th ed, Prentice Hall, 1999)

- VIII. Michael Padilla et al., Focus on Life Science: California Edition (Prentice Hall, 2001)

- IX. Kenneth R Miller & Joseph Levine, Biology: The Living Science (Prentice Hall, 1998)

- X. Kenneth R Miller & Joseph Levine, Biology (4th ed., Prentice Hall, 1998)

*Note: some paragraphs are the same because some textbooks re-use the same material in different editions.

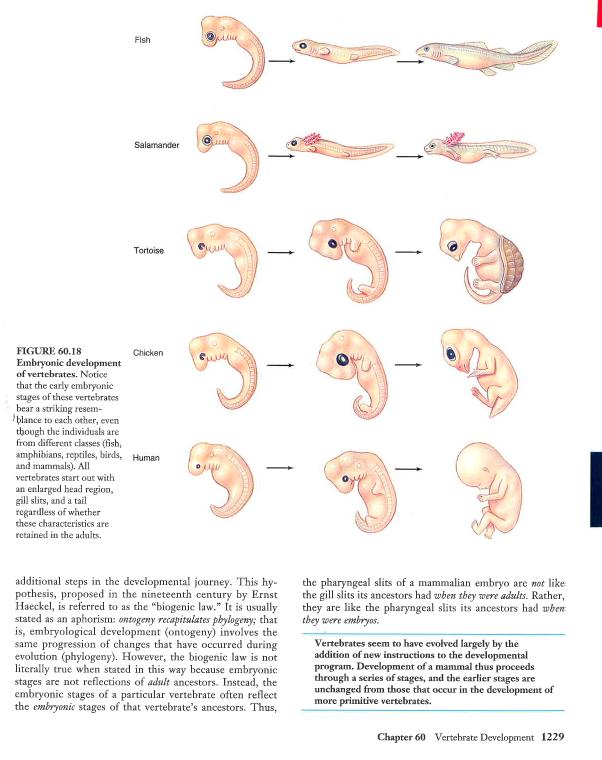

Textbook I. Peter H Raven & George B Johnson, Biology (5th ed, McGraw Hill, 1999), pp. 416, 1181:

Analysis: (1) As seen here, the textbook uses a colorized and slightly edited version of Haeckel’s original fraudulent drawings. This version obscures the differences between the earliest stages of embryos as egregiously as Haeckel’s original drawings did.

(2) The drawings are presented as valid evidence for the modern theory of evolution, and are not merely used to provide historical context. They come from a section entitled “Embryonic Development and Vertebrate Evolution.” The caption reads: “Embryonic development of vertebrates. Notice that the early embryonic stages of these vertebrates bear a striking resemblance to each other, even though the individuals are from different classes (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). All vertebrates start out with an enlarged head region, gill slits, and a tail regardless of whether these characteristics are retained in the adult.” (p. 1181) The text states: “The patterns of development in the vertebrate groups that evolved most recently reflect in many ways the simpler patterns occurring among earlier forms. Thus, mammalian development and bird development are elaborations of reptile development, which is an elaboration of amphibian development, and so forth (figure 58.16).” (p. 1180) Although Haeckel is mentioned, it is clear that the textbook authors regard these drawing as evidence apart from Haeckel’s interpretation.

(3) The text not only discusses “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” but also affirms it, albeit in a slightly different form. This entire discussion comes from a subsection entitled “Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny,” in which the authors repudiate Haeckel’s claim but then defend a reformulated version of it: “The developmental instructions for each new form seem to have been layered on top of the previous instructions, contributing additional steps in the developmental journey. This hypothesis, promoted in the nineteenth century by Ernst Haeckel, is referred to as the ‘biogenetic law.’ It is usually stated as an aphorism: ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny; that is, embryological development (ontogeny) involves the same progression of changes that have occurred during evolution (phylogeny). However, the biogenetic law is not literally true when stated in this way because embryonic stages are not reflections of adult ancestors. Instead, the embryonic stages of a particular vertebrate often reflect the embryonic stages of that vertebrate’s ancestors.” (p. 1180, emphases in original) Earlier the text stated: “In many cases, the evolutionary history of an organism can be seen to unfold during its development, with the embryo exhibiting characteristics of the embryos of its ancestors.” (p. 416) The basis for the text’s claims that the law holds is the fraudulent Haeckel-derived drawings, which obscure the differences between the embryos.

Textbook II. Peter H Raven & George B Johnson, Biology (6th ed, McGraw Hill, 2002), p. 1229:

Analysis: (1) As seen here, the 6th edition of this textbook simply recycles the same drawings used in the 5th edition (text I, discussed above).

(2) The text accompanying the drawings is also the same as that of 5th edition, though on different pages (1228-1229 and 450 instead of 1180-1181 and 416). As in the 5th edition, Haeckel is mentioned, but it is clear that the authors still regard these drawing as valid evidence for evolution that is untainted by Haeckel’s fraud. The authors also continue to claim that “embryonic stages of a particular vertebrate often reflect the embryonic stages of that vertebrate’s ancestors.”

(3) As in the 5th edition, the text reaffirms a reformulated version of Haeckel’s law of recapitulation, using the same text. The entire basis for the text’s affirmation of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is the fraudulent Haeckel-derived drawings, which obscure the differences between the early stages of embryos.

Textbook III. Douglas J. Futuyma, Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed, Sinauer, 1998), p. 653:

Analysis: (1) Haeckel’s original faked drawings are shown with a caption implying that vertebrate embryos are very similar at early stages: “An illustration of von Baer’s law: three stages in the development of several vertebrates. All the vertebrates share many common features early in development; many distinguishing features of the classes and orders appear later.” (p. 653) There is no indication that the drawings are fraudulent.

(2) The caption states that the picture supports common descent and evolution. There is no indication in the caption that this is merely a part of history, but there is every indication that this is how embryos really look and that the drawings provide evidence for the modern theory of evolution.

(3) The book contains about a page of text discussing “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” noting that the law “rather seldom holds” but implying that it still has relevance to modern biology: “There are, to be sure, many cases in which certain features of an ancestor are recapitulated in the ontogeny of a descendant … the biogenetic law is honored more often in the breach than in the observance, and it is certainly not an infallible guide to phylogenetic history.” (pp. 652-653)

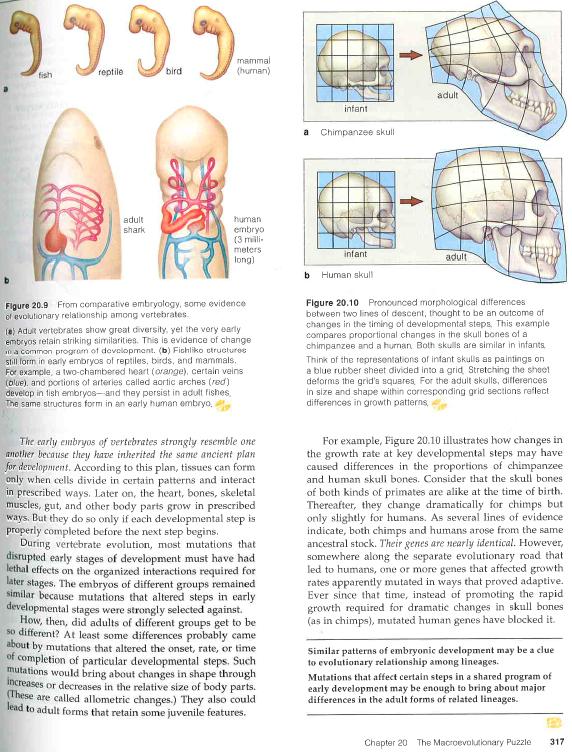

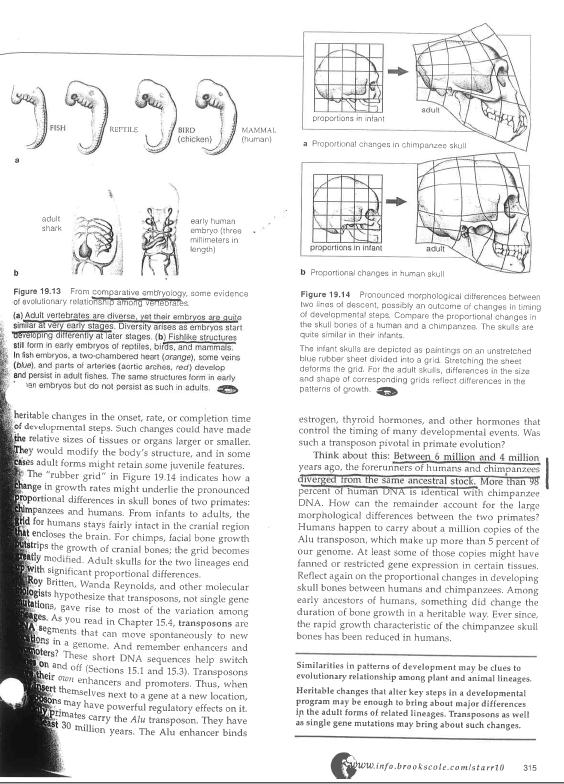

Textbook IV. Cecie Starr and Ralph Taggart, Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (8th ed, Wadsworth, 1998), p. 317:

Analysis: (1) This textbook uses colorized versions of drawings derived from Haeckel’s earliest embryo stages that obscure the differences between the embryos.

(2) The caption implies that this is still valid evidence for the modern theory of evolution, There is no indication that this line of reasoning comes merely from history. The textbook states: “From comparative embryology, some evidence of evolutionary relationships among vertebrates. … Adult vertebrates show great diversity, yet the very early embryos retain striking similarities” … The early embryos of vertebrates strongly resemble one another because they have inherited the same ancient plan for development.” (p. 317, emphasis in original) The entire discussion is in the section “Evidence from Comparative Embryology” and states, “Strong evidence of evolution comes from anatomical comparisons of major lineages.” (p. 316)

(3) Haeckel’s recapitulation theory is not discussed.

Textbook V. Joseph Raver, Biology: Patterns and Processes of Life (J.M.Lebel, 2004, draft version presented to the Texas State Board of Education for approval in 2003), p. 100:

Analysis: (1) The text displays a graphic derived from Haeckel’s original drawings, which fraudulently obscure nearly all of the differences between the various embryo forms.

(2) The caption reads, “All vertebrate embryos closely resemble one another in early development.” (p. 100) The implication is that this provides evidence for common ancestry.

(3) Haeckel’s notion that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed.

(Note: Only after Discovery Institute and Texans for Better Science Education repeatedly complained to the Texas State Board of Education about this reuse of Haeckel’s inaccurate drawings did the publisher eventually agree to remove them from this textbook.)

Textbook VI. Cecie Starr and Ralph Taggart, Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (Wadsworth, 2004, draft version presented to the Texas State Board of Education in 2003), p. 315:

Analysis: (1) The text displays a graphic derived from Haeckel’s original drawings, and fraudulently obscure most of the differences between the various embryo forms.

(2) The text intends for this graphic to be taken as support for evolution, and not merely to provide historical context. The caption reads, “From comparative embryology, some evidence of evolutionary relationship among vertebrates. (a) Adult vertebrates are diverse, yet their embryos are quite similar at early stages.” The section is titled “Evidence From Patterns of Development” with the subheading “Developmental Program of Vertebrates.” The text reads, “The early embryos of vertebrates strongly resemble one another because they inherited the same ancient plan of development.” (p. 315, emphasis in original)

(3) Haeckel’s idea of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed.

(Note: Only after Discovery Institute and Texans for Better Science Education repeatedly complained to the Texas State Board of Education about this reuse of Haeckel’s inaccurate drawings did the publisher eventually agree to remove them from this textbook.)

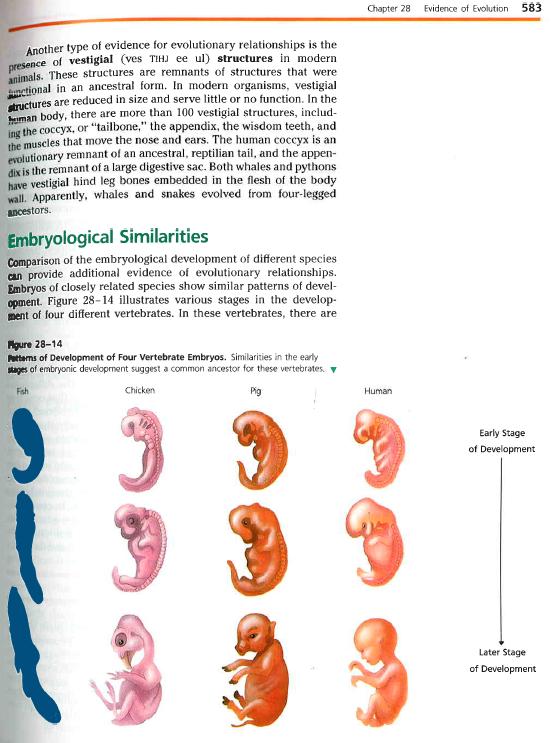

Textbook VII. William D. Schraer and Herbert J. Stoltze, Biology: The Study of Life (7th ed, Prentice Hall, 1999), p. 583:

Analysis: (1) This drawing is not as bad as the others, but is still clearly derived from Haeckel’s drawings. (For example, the newborn chicken in this graphic is nearly identical to the newborn chicken in Haeckel’s drawings.) The differences between embryos are obscured, though not to the extent that Haeckel obscured them.

(2) The section uses the drawings as evidence for the modern theory of evolution, stating in the caption: “Similarities in the early stages of embryonic development suggest a common ancestor for these vertebrates.” (p. 583) The diagram comes from the chapter “Evidence for Evolution” in a section entitled “Evidence from Living Organisms” in a subsection entitled “Embryological Similarities.”

(3) Haeckel’s idea of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed.

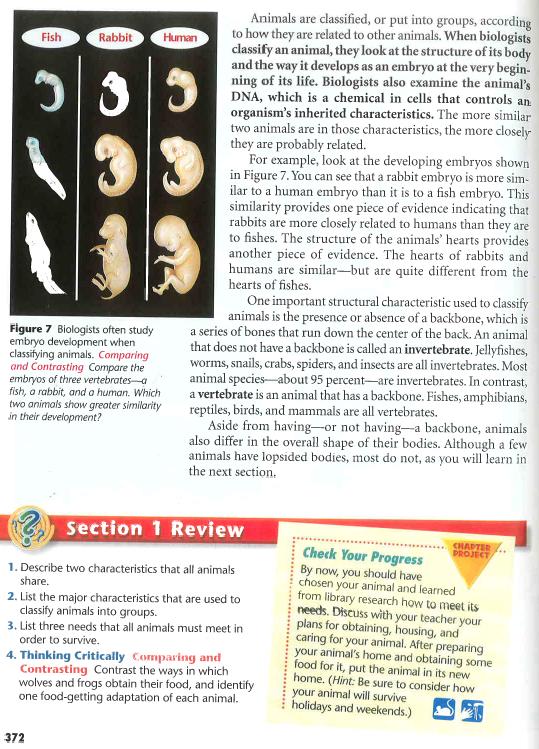

Textbook VIII. Michael Padilla et al., Focus on Life Science: California Edition (Prentice Hall, 2001), p. 372:

Analysis: (1) The text uses a graphic which is essentially a colorized adaptation of Haeckel’s original drawings, and it obscures the differences between early embryos just as much as Haeckel did.

(2) The text treats the graphic as evidence for the modern theory of supports evolution, and there is no indication that the discussion is to be taken merely in historical context: “Animals are classified, or put into groups, according to how they are related to other animals. When biologists classify an animal, they look at the structure of its body and the way it develops as an embryo at the very beginning of life. … The more similar two animals are in those characteristics, the more closely they are probably related. For example, look at the developing embryos in Figure 7. You can see that a rabbit embryo is more similar to a human embryo than it is to a fish embryo. This similarity provides one piece of evidence that rabbits are more closely related to humans than they are to fishes.” (p. 372, emphases added)

(3) Haeckel’s idea of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed.

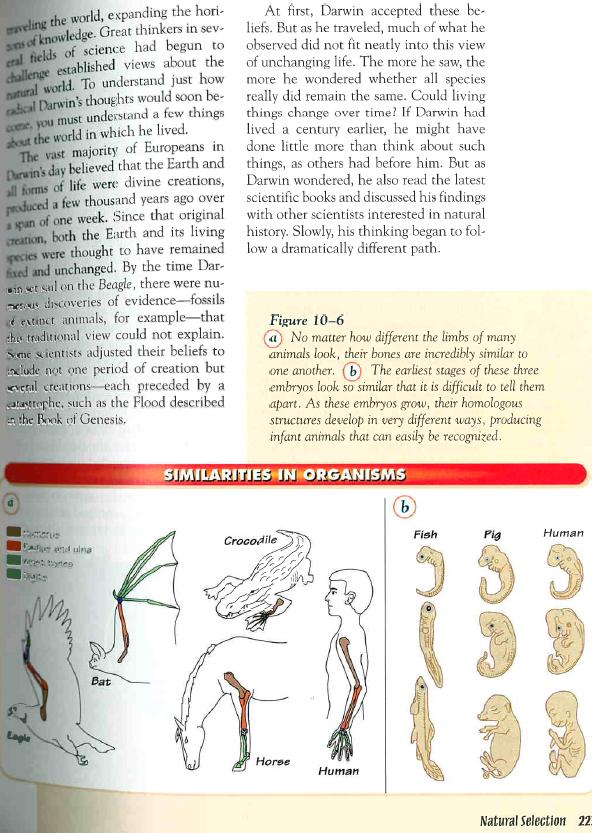

Textbook IX. Kenneth R Miller & Joseph Levine, Biology: The Living Science (Prentice Hall, 1998), p. 223:

Analysis: (1) This textbook uses colorized Haeckel-type drawings that minimize the differences between early embryo stages, promoting the view that vertebrate embryos are extremely similar and therefore share a common ancestor. Although the drawings have been redone, they closely resemble those of Haeckel.

(2) The text treats these drawings as valid evidence for the modern theory of evolution, stating: “The earliest stages of these three embryos look so similar that it is difficult to tell them apart” (p. 223), and again on the next page, “As you can also see, studies of developing embryos revealed even more surprising similarities.” (p. 224) This is from the chapter on “Natural Selection,” from the section entitled “A Riddle: Life’s Diversity and Connections.” The presentation is not about historical context.

(3) Haeckel’s idea of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed.

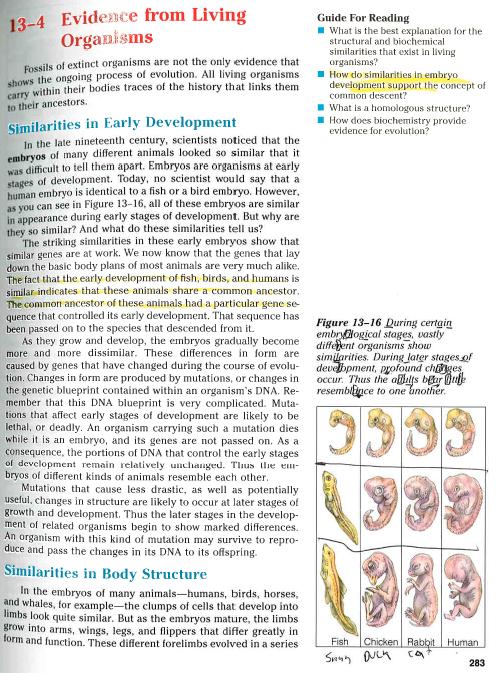

Textbook X. Kenneth R Miller & Joseph Levine, Biology (4th ed., Prentice Hall, 1998), p. 283:

Analysis: (1) This textbook uses colorized drawings patterned after Haeckel’s, and like Haeckel’s they obscure the differences between early embryo stages.

(2) Although the textbook mentions misconceptions of nineteenth century biologists, the drawings themselves are clearly treated as valid evidence for the modern theory of evolution: “However, as you can see in Figure 13-16, all of these embryos are similar in appearance during early stages of development.” (p. 283) The caption reads: “During certain embryological stages, vastly different organisms show similarities. During later stages of development, profound changes occur. Thus the adults bear little resemblance to one-another.” (p. 283) The section is titled “Evidence from Living Organisms” and introduces the embryo drawings with: “Fossil evidence of extinct organisms are not the only evidence that shows the ongoing process of evolution.” (p. 283)

(3) Haeckel’s idea of “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is not discussed. Although the textbook acknowledges that biologists today would not say that the embryos are “identical,” it obviously regards them as similar enough to provide evidence for evolution – and their similarities are exaggerated in much the same way Haeckel exaggerated them.