The Hidden Crisis in the Woods

View at YouTubeFor months now, I’ve been tracking and looking into multiple homeless encampments across Seattle and King County.

“We’re working hard in this area. Probably harder than you’ve seen in recent years,” says Mayor Bruce Harrell as he unveiled his homelessness dashboard last month.

City and state agencies are finally taking aggressive action, clearing some of the largest and most visible encampments on public property.

Governor Jay Inslee recently said homeless people who refuse to leave state land along highways could be fined. “You will need to move. You just have to follow the law. You can’t be continuing to create these safety hazards on our right-of-ways,” he says.

While officials say most campers are accepting services and shelter, some are refusing and choosing to stay on the streets. “I do better out here, you know what I mean,” says Marcus Weatherspoon, who was recently forced to leave an encampment in Ballard.

There’s another segment of the homeless community who are creating a crisis in the woods, preferring to stay hidden in these lush havens.

“I don’t want predators around me,” says homeless Kaylee Gordon. She says after the city’s recent crackdown on illegal camping, she’s seeing more of her friends escaping to these areas from living on the streets. “I feel safe, yeah. That’s the reason I keep coming back out here,” says Gordon.

Gordon is also trying to stay out of sight and out of mind. “I’m the type of person who likes to stay away from people,” she says.

The movement from city streets to wooded areas is creating unintended consequences. Here in West Seattle, massive wooden structures, abandoned tents, mounds of trash, and needles litter this hillside off Detroit Avenue SW.

At nearby South Seattle College, this opening near the Seattle Chinese Garden leads into the West Duwamish Greenbelt, which is now a complicated network of pathways covered in garbage and drug paraphernalia.

Analissa Lafayette, who lives nearby, says she’s not sure how many campers are using this site. “It’s pretty apparent once a site gets established, you not only have folks coming back and forth, but new folks coming back and forth,” she says. But no one was around the site when we visited.

Lafayette notes, “There are going to be people who choose to stay homeless,” but she’s concerned for their safety but also the environmental impact.

She wants city and state agencies to take immediate action: “Let’s track it. Let’s see what’s happening.”

At this pond in White Center, the signs say it’s a wetland and considered fragile habitat for all kinds of wildlife.

“It’s a King County natural area — a sensitive area, an environmentally sensitive area,” says Vivian McPeak. He says it’s being illegally used by homeless people to hang laundry, cook food, and pitch tents.

Sympathetic to their plight, he says, “Everybody needs a place to stay. They need to camp somewhere. But not in an environmentally protected area.”

After a short walk, we met this man who only wants to be called Muhammed, who’s building a hut with a thatched roof. McPeak says he’s concerned fresh trees are being cut down: “This person’s been sawing off trees, limbs, a lot of them.”

But Muhamed says he’s simply using lifeless branches and plans on staying in this encampment for the long run, even if the county comes by and tries to move him.

“The county, King County, that’s mine. That’s mine, that’s mine,” says Muhamed.

And in unincorporated King County just outside of Kent, the woods off Green River Road are full of majestic trees. But from the inside, it looks like a disaster.

Some of the waterways are clogged with debris. And there are dozens of bicycles, broken tents, and other personal belongings scattered throughout.

Wittney Silvera is homeless and says she’s intentionally living here with her boyfriend. “We all know each other. It’s like a family out here,” she says.

Hoping the area can continue to give them some cover, she says, “I don’t have to worry about people harassing you on the street or looking at you as less than.”

Silvera estimates more than 30 people stay within this network of trails. “I know there’s a lot more on the other side. On the back, on the other side over there,” she says.

With ongoing encampment clean ups across the state, Silvera also says she’s seeing more homeless people retreating into the woods: “I’ve seen a lot of different people coming in and out. There’s lot of the same people here, but I’ve noticed that quite a bit actually.”

But right now, it’s unclear if anyone truly knows the magnitude of this problem.

Seattle unveiled it’s new homelessness dashboard last month. But it does not show exact locations of encampments, especially in the woods. And there’s nothing like what you see here in other counties or at the state level.

As I walked deeper into the vast forest, I discovered even more campsites with clear signs of life. However, no one else responded.

After more than an hour of exploring, I met this man who lives nearby.

Fearing retaliation from the people living in the woods, he wants to remain anonymous. He speaks about the problems created by the unhealthy environment. He says just in the past few months, firefighters have trekked through the constellation of trails to put out flames started by the homeless.

“And the fire department’s gone up for OD’d victims,” says this neighbor. “And when they come back down, their hoses are literally been drug through feces, urine, and everything else. So they have to spend three hours down at the street, washing their hoses.

So far this year, Puget Sound Fire has responded to dozens of medical emergencies in the woods, including seven fires. But a department spokesperson says he’s not sure how many are actually related to the homeless community.

As I exited through an opening, it led me back on to Green River Road. An area lined with RV’s, and even more piles of trash.

The King County Sheriff’s Office says it’s become a notorious “chop shop” for stolen cars, but cautions against blaming the homeless for all the problems.

Stephen Rubio lives in one of the vehicles. He complains about being “unfairly blamed, saying we’re the ones doing it.”

Off the banks of the nearby Green River, several campers have established their own version of waterfront property, setting up tents, beds, and everything else they need to hunker down.

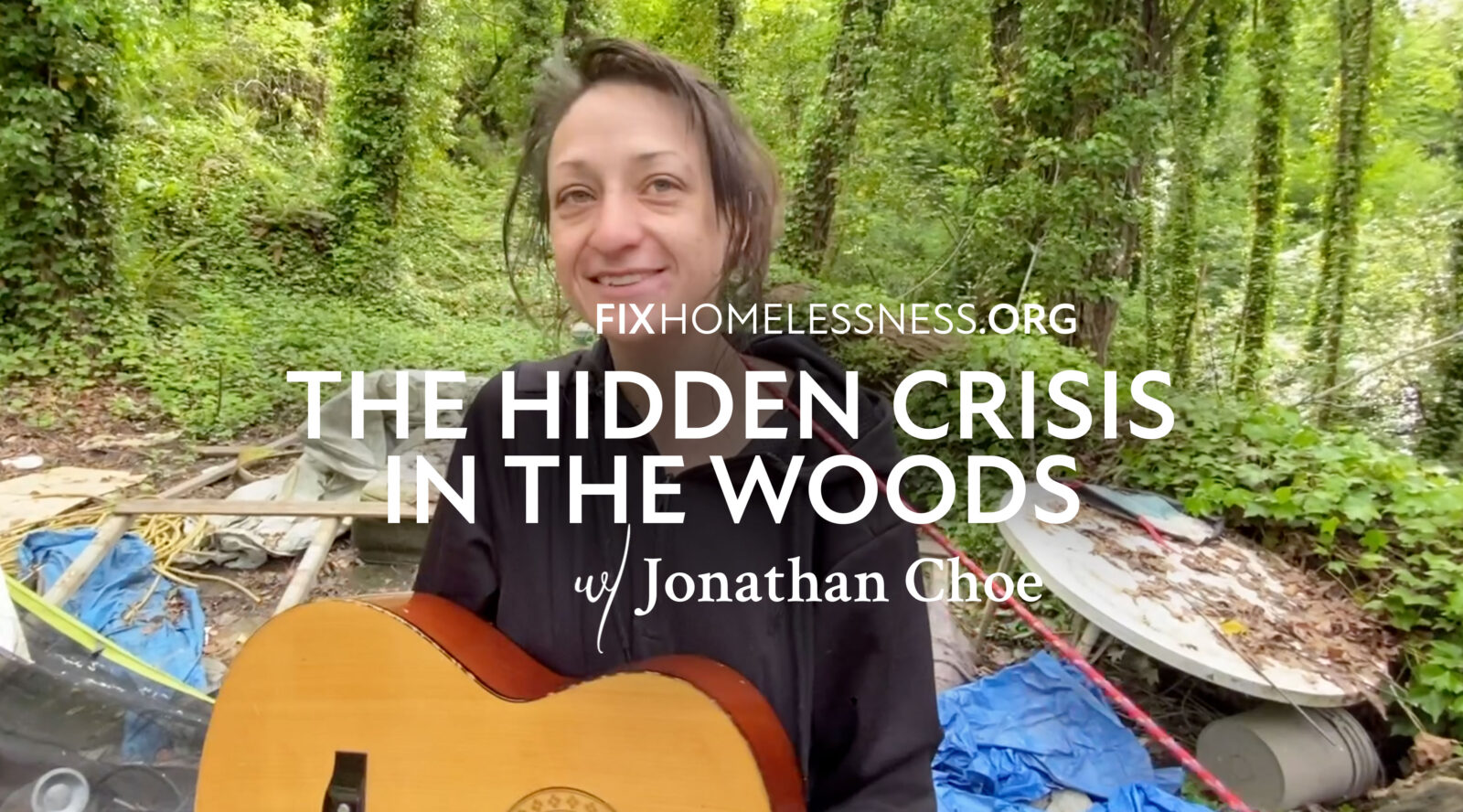

Back in West Seattle, Gordon showcases her gift as a musician and displays enormous potential. But admits she’s also struggling with an addiction to hard drugs. “Heroin was always my DOC,” she says.

Her music and these woods now provide a refuge and temporary escape from the pain.

Gordon laments, “There are a lot of things going on with my life.”

Coming up in part two of our series …

Neighbors, community advocates, and elected officials see the problem, including King County Councilmember Reagan Dunn.

“Well it’s like the Third World out here in the woods. It’s tragic, it’s utterly tragic,” says Dunn.

But right now, very little is being done about this crisis in the woods. What’s the hold up? Who’s taking responsibility, and what are the immediate and long-term solutions?