Tom Shakely is a Research Fellow with Discovery Institute's Center on Human Exceptionalism, where he focuses on human dignity, human rights, and law and policy. Tom also serves as Chief Engagement Officer at Americans United for Life, a national leader in advancing life-affirming law and policy, where he hosts "Life, Liberty, and Law," featuring conversations on the human right to life.

Tom previously served as Executive Director of the Terri Schiavo Life & Hope Network, whose Crisis Lifeline serves patients and families facing denial of basic care and strives to awaken the conscience on human dignity and bioethical issues.

Tom has spoken on human rights issues at the United Nations, testified to the District of Columbia City Council on conscience rights, and advised on testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee and U.S. House of Representatives. Tom is a member of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities and Knights of Columbus, and is a Charlotte Lozier Institute guest contributor and a Sons of the American Revolution life member. Tom serves as a board member for the Mount Nittany Conservancy and has previously served as a board member for the Pro-Life Union of Greater Philadelphia and as an at-large member of Archbishop Charles J. Chaput’s Archdiocesan Pastoral Council in Philadelphia, as well as a National Review Institute Washington fellow and as a Leonine Forum fellow.

Tom holds a B.A. in Political Science from the Pennsylvania State University, M.S. in Bioethics from the University of Mary, and Certification with Distinction in Health Care Ethics from the National Catholic Bioethics Center. Tom has written for National Review, HuffPost, National Catholic Register, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and other nationally recognized media.

Archives

A Time for Choosing on Roe and the Abortion Regime

The Supreme Court and American Independence from Abortion

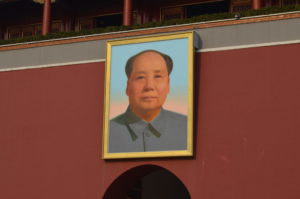

China, Human Rights, and Washington’s Lack of Strategy

What Comes After Margaret Sanger’s Cancelation?

Carter Snead on the Fundamental Disagreement of Our Time: What a Person Is

Independence Day and Renewed Vigor

‘The Committee Heard From People Who Had Made Plans for Suicide’

What If We Ignored Those Most Vulnerable to COVID-19?

Reimagining Home Life Instead of Warehousing Our Elders

On China, Human Rights, and ‘Making a Pyromaniac Into the Town Fire Chief’

Autonomy, Ezekiel Emanuel, and the Limits of Advance Directives

China, the Virus, and the Imperative to Build for Tomorrow

Taiwan ‘Didn’t Trust Either the Chinese Government or the Head of the World Health Organization’

Bloomberg: A Patient’s Care is ‘Futile’ if We Decide the Patient Has Little Value

Making Something Lawful Creates a Market for It

In Canada, No Need to be ‘End of Life’ in Order to End Life

Suicide Prevention Means Rejecting Suicide Assistance

‘Rights Talk’