Archives

A Christian Approach to Treating Fentanyl Addiction

What Happens With Homelessness When FEMA Doesn’t Come?

In the WSJ: A Christian Approach to Treating Fentanyl Addiction

Homeless by Tornado

Heartless in San Francisco

Eight days in the Golden State. First in a Series.

Enticing People to Change

Mixed Messages on Homelessness

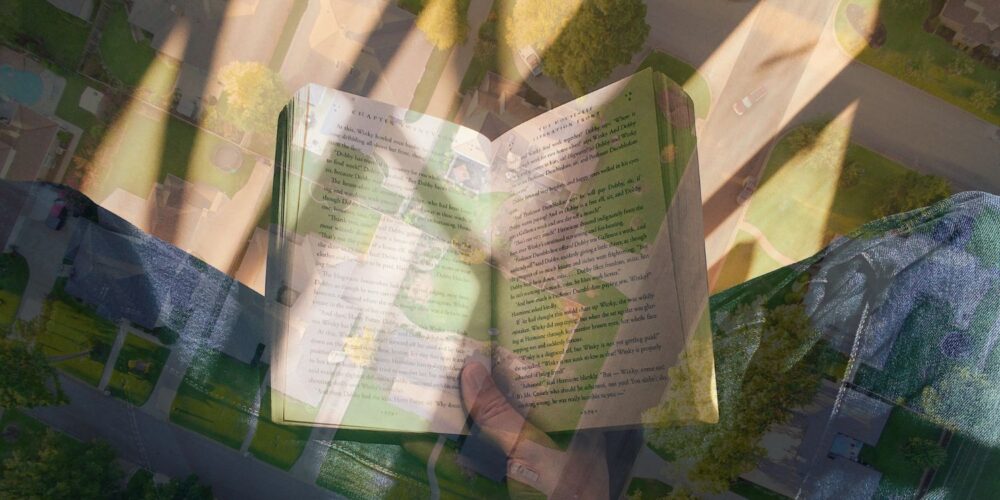

Homeless in Seattle — in fiction

Kings of the Road, Homeless Heroes, Noble Savages

Buying Prayers, Building Cathedrals

Help the Homeless, Help Yourself?

After Reading Current Assumptions, Try Some Wisdom From the Past

Ranking Alternative Ways to Fix Homelessness

Understanding the Homeless Debate

Homelessness and the Rushing Wind

Where Are They Now?

Five books on homelessness