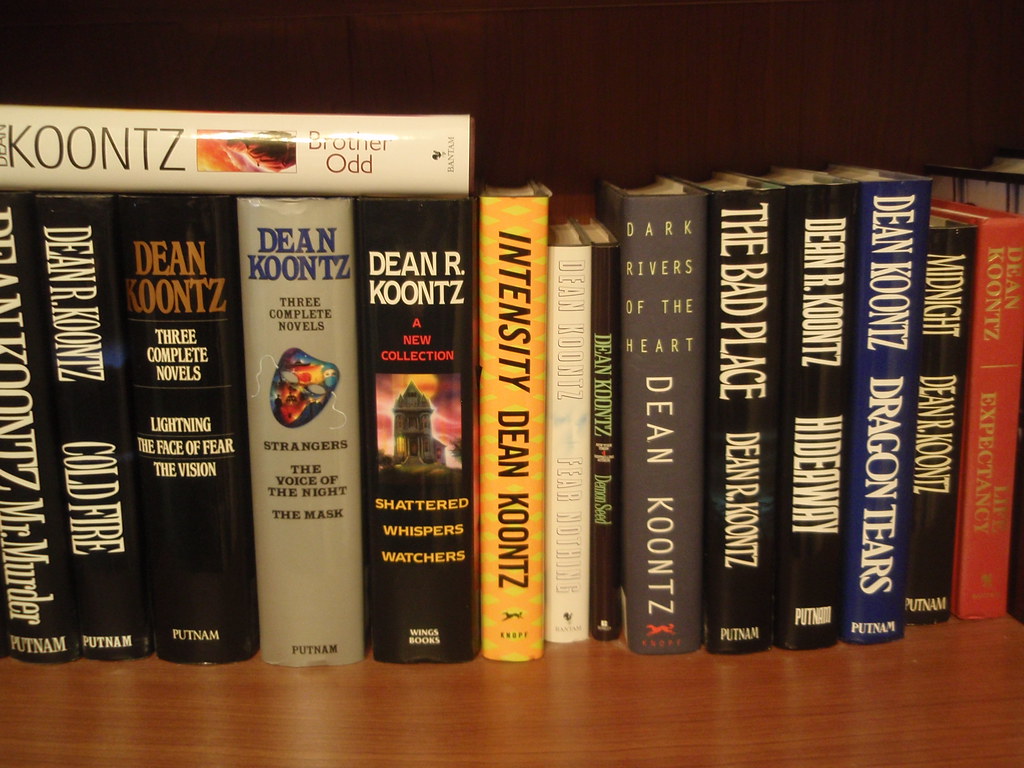

Why You Should Binge Read Dean Koontz

His novels are a rollicking good time, spiced with powerful social commentary that stands unapologetically for righteousness and human liberty. Crossposted at HumanizeIt’s hard not to binge read a Dean Koontz novel. Koontz’s prose is beyond tight. His suspenseful plots hurl readers headlong into raucous adventures in which the stakes for his protagonists are extreme and, for humanity, often dire. His heroes are resilient. His villains ooze wickedness. Walk-on characters are often hilarious, and indeed, Koontz’s sharp sense of humor distinguishes him from most other contemporary mega-selling novelists.

Koontz’s path to world fame was not easy. He grew up destitute in Pennsylvania in a house that for much of his childhood did not have running water. He recalls that his abusive father was “the town drunk,” a “womanizer and gambler who defrauded people. Each time he hit bottom, he talked of suicide — and of taking my mother and me with him.”

But Koontz persevered. After he married his high school sweetheart Gerda, he settled in as an English teacher. But at Gerda’s urging, he soon quit to pursue his dream of becoming a novelist and never looked back. He has sold an astonishing 500 million-plus books, published in 38 languages, with 14 of his novels listed as number-one hardcover best sellers on the New York Times list.

One doesn’t become that wildly successful over decades by accident. Koontz is extremely disciplined, writing many hours a day and continually seeking to hone his craft. He also is an inveterate researcher. When he describes a locale or the workings of, say, computers, biotechnology, or guns, he weaves factual information into his fictional accounts seamlessly. About this aspect of his technique, Koontz told me:

When it comes to getting details right, I am the next thing to an obsessive-compulsive personality. I don’t want to look like a fool — but also because faking even small details undermines the credibility and worthwhile intentions of the entire work.

None of that accuracy would matter if his books weren’t supremely enjoyable. First and foremost, Koontz is an entertainer. To do otherwise, he told me, would be to mutate fiction into “propaganda.” And while most of his novels are thrillers filled with dark foreboding, they are also a lot of fun. Walk-on characters are often hilariously eccentric, and even his villains can have quirky personalities that make one guffaw. He also can write very sweetly. He clearly has a soft spot for people with special needs, who sometimes are the most courageous of his characters. Koontz is also a passionate dog lover, and so it isn’t surprising that he often includes a canine character along for the ride as an exemplar of purity and innocence.

If an enjoyable read was all there was to Koontz’s work, it would be enough. But like the best novelists, Koontz also communicates important moral truths. His individual stories may be comedic or dark; they may involve the supernatural or monsters distinctly of the human realm. But they all share a consistent perspective about the primacy of personal character in life outcomes. Indeed, his heroes and villains act according to clear and contrasting moral codes that impact their respective fates in profound ways.

Koontz told me that these sharp character contrasts are intentional:

These days, literary and popular culture frequently glamourize evil. I never do. My antagonists are terrifying but also often unconsciously amusing, capable of great cruelty but foolish because of their self-adoration and psychopathic confidence. Impressionable individuals in my audience are unlikely to seek to emulate fools.

As to his heroes: “On the other hand, my protagonists are flawed people who endure misfortune and suffering without bitterness or self-pity. I like to think their fortitude and unshakable hope might inspire the same in readers, for those are some of the rewards of faith.” (It is worth noting here that Koontz is an orthodox Catholic.)

Koontz’s fiction mounts a powerful defense of the importance of human dignity.

The most virtuous of Koontz’s conjured characters has to be Odd Thomas, a somewhat peculiar young fry cook who can see ghosts and (invisible to most people) demonic phantoms called “bodachs” that swarm locales of pending evil events as so many omens of death. Over the course of an eight-novel series, Odd becomes increasingly self-sacrificing as he risks his own life to protect the vulnerable against malevolent forces — and during his story arc interacts with some very famous deceased personages. He is hilariously mooned by the specter of LBJ, helps the ghost of Elvis Presley reach the great beyond, and is aided in a time of peril by poltergeist actions of Frank Sinatra. But the true through line of the Odd Thomas series is about the power of abiding love. You will have to read all the books to get how deeply that romantic thread runs.

Koontz’s various stories also provide a running commentary on the sorry state of contemporary American culture, in particular, the egregious failings of our most important cultural institutions and the irresponsibility of our woke leadership class. The perils of transhumanism and the threats to liberty posed by a technologically empowered intrusive national security state are other sources of inspiration, as his plots often involve the catastrophic consequences of hubristic science gone wrong and/or imperiled protagonists having to shed the accoutrements of modernity in order to evade detection by the many methods available to track us as we go about our daily lives.

In this, Koontz — who, full disclosure, is a close friend — is not paranoid. The growing technological prowess of an intrusive national security state — which is particularly the focus of his Jane Hawk series — is not a figment of his fecund imagination. Koontz told me:

All the tracking technology in the Jane Hawk books is real. The navigation systems in our cars are also tracking devices that allow the state to follow our every move. Our smartphones are tracking devices that provide a history of our movements even when they’re switched off.

Why worry about all that? Koontz explained:

As technology advances — and if AI doesn’t destroy us before it facilitates our enslavement — our only hope of avoiding the most oppressive tyranny in history will be to rediscover, as a society, the forgotten truth that our rights are God-given, that our gratitude and hope should be directed toward our creator rather than toward the state.

Dean Koontz novels are many things. Incredibly entertaining. Superbly suspenseful. Often bitingly satirical and sometimes very funny. But they are also deep and thoughtful. Rather than celebrate the transgressive and glamorize the nihilistic as many novelists do today, Koontz’s fiction mounts a powerful defense of the importance of human dignity and the power inherent in the virtues. They also serve as a sharp warning about the temptations of evil. Of this he said:

As our culture has sunk into a bog of therapeutic nonsolutions and wistful utopian dreams, the existence of evil has been denied except as an accusation against political enemies. The most terrible acts and corruption are said to have treatable or at least understandable psychological origins or to be a result of social injustice. I don’t live — or write — under those illusions, because during the 17 years when I lived in my father’s shadow, I saw that evil is an option which people so inclined will choose not with desperation but with delight.

If you want a rollicking good time spiced with powerful social commentary that stands unapologetically for righteousness and human liberty, a Dean Koontz novel fills the bill. But be forewarned. Once you start reading, you won’t want to stop until the last page is turned.