Do Car Engines Run on Lugnuts? A Response to Ken Miller & Judge Jones’s Straw Tests of Irreducible Complexity for the Bacterial Flagellum

Original ArticleCopyright © 2006 Casey Luskin. All Rights Reserved.

A PDF of this article can be read here.

Abstract

In Kitzmiller v. Dover, Judge John E. Jones ruled harshly against the scientific validity of intelligent design. Judge Jones ruled that the irreducible complexity of the bacterial flagellum, as argued by intelligent design proponents during the trial, was refuted by the testimony of the plaintiffs’ expert biology witness, Dr. Kenneth Miller. Dr. Miller misconstrued design theorist Michael Behe’s definition of irreducible complexity by presenting and subsequently refuting only a straw-characterization of the argument. Accordingly, Miller claimed that irreducible complexity is refuted if a separate function can be found for any sub-system of an irreducibly complex system, outside of the entire irreducible complex system, suggesting the sub-system might have been co-opted into the final system through the evolutionary process of exaptation. However, Miller’s characterization ignores the fact that irreducible complexity is defined by testing the ability of the final system to evolve in a step-by-step fashion in which function may not exist at each step. Only by reverse-engineering a system to test for function at each transitional stage can one determine if a system has “reducible complexity” or “irreducible complexity.” The ability to find function for some sub-part, such as the injection function of the Type III Secretory System (which contains approximately ¼ of the genes of bacterial flagellum), does not negate the irreducible complexity of the final system. Moreover, Miller ignored the fact that any evolutionary explanation of a system must account for much more than simply the availability of the parts. In the final analysis, Miller’s testimony did not actually refute irreducible complexity, leaving readers of the Kitzmiller ruling with the unfortunate perception that the evolutionary origin of the bacterial flagellum has been solved.

Introduction: The Definition of Irreducible Complexity

Design theorist and biologist, Michael Behe, defines “irreducible complexity” by looking at a biological system to see if it can be produced in a step-by-step evolutionary fashion. Behe defines irreducible complexity in his book Darwin’s Black Box:

“In The Origin of Species Darwin stated:

‘If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.’

A system which meets Darwin’s criterion is one which exhibits irreducible complexity. By irreducible complexity I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning.”

(Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, p. 39 (Free Press, 1996) (emphasis added).)

During the Kitzmiller trial, Michael Behe testified in favor of intelligent design by arguing that the bacterial flagellum represents one such biological structure which is irreducibly complex. The bacterial flagellum is a motor-driven propeller for bacterial swimming. (For a technical discussion of the various components of the bacterial flagellum, see David J. DeRosier, Spinning Tails, Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 5:187-193 (1995).) In the Kitzmiller trial, however, Judge Jones’ ruling disagreed with Behe’s claims and alleged that Behe ignored how evolution can effectively produce complex structures like the bacterial flagellum:

“Drs. Miller and Padian testified that Professor Behe’s concept of irreducible complexity depends on ignoring ways in which evolution is known to occur. Although Professor Behe is adamant in his definition of irreducible complexity when he says a precursor “missing a part is by definition nonfunctional,” what he obviously means is that it will not function in the same way the system functions when all the parts are present. For example in the case of the bacterial flagellum, removal of a part may prevent it from acting as a rotary motor. However, Professor Behe excludes, by definition, the possibility that a precursor to the bacterial flagellum functioned not as a rotary motor, but in some other way, for example as a secretory system.” (Kitzmiller ruling, p. 74. All references to Kitzmiller ruling from Judge Jones original ruling, here)

What follows is an assessment of the Judge’s findings with respect to the irreducible complexity of the bacterial flagellum.

Ignoring Exaptation?

In the Kitzmiller ruling, Judge Jones uses the term “exaptation” (also called “co-option,” or “preadaptation”) to describe how a part may initially serve a role in the cell, only to be later employed by an irreducibly complex system to perform some different function. The widely used college text Evolutionary Biology describes exaptation as follows:

“Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth Vrba (1982) suggest that if an adaptation is a feature evolved by natural selection for its current function, a different term is required for features that, like the hollow bones of birds or the sutures of a young mammal’s skull, did not evolve because of the use to which they are now put. They suggest that such characters that evolved for other functions, or for no function at all, but which have been co-opted for a new use be called exaptations.” (Douglas J. Futuyma, Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed. 1998), p. 355 (emphasis in original).)

Judge Jones alleges in his ruling that Michael Behe ignores exaptation as a way of accounting for the origin of biological complexity:

“By defining irreducible complexity in the way that he has, Professor Behe attempts to exclude the phenomenon of exaptation by definitional fiat, ignoring as he does so abundant evidence which refutes his argument.” (Kitzmiller ruling, p. 76.)

Judge Jones’s claim that Behe ignores “exaptation” was based upon the testimony of Dr. Kenneth R. Miller, an evolutionist and the plaintiff’s lead-expert biology witness during the trial. Dr. Miller testified that irreducible complexity is refuted if one can find any use for some sub-part of the total system:

“Dr. Behe’s prediction is that the parts of any irreducibly complex system should have no useful function. Therefore, we ought to be able to take the bacterial flagellum, for example, break its parts down, and discover that none of the parts are good for anything except when we’re all assembled in a flagellum.” (Dr. Kenneth Miller Testimony, Day 1, PM Session, page 16.)

Miller’s characterization of irreducible complexity is grossly inaccurate. In particular, Miller applied his argument to real biological situations when he claimed that some sub-systems of the bacterial flagellum can perform a different role in some organisms. For example, Miller observed that the Type III Secretory System (TTSS), which uses approximately 1/4 of the genes involved in the flagellum, can be used by predatory bacteria to inject toxins into Eukaryotic cells. (See Scott A. Minnich and Stephen C. Meyer, Genetic Analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic

bacteria, p. 8, at https://www.discovery.org/f/389.) According to Miller, the presence of the TTSS shows that the bacterial flagellum is not irreducibly complex. However, Miller’s Type III Secretory System argument contains three primary problems:

(A) Experts say the evidence suggests that the TTSS evolved from the flagellum, and not the other way around.

(B) Behe and other ID-proponents have long-acknowledged “exaptation” or “co-option” as an attempt to evolve biological complexity, and have observed many problems with “co-option” explanations.

(C) Miller has inaccurately characterized how one tests for irreducible complexity, thus refuting only a straw-version of Behe’s concept of irreducible complexity.

(A) Which came first: the TTSS or the Flagellum (or neither)?

Firstly, it is worth noting that a leading authority on bacterial systematics, Milton Saier, still believes that TTSS evolved FROM the flagellum, not the other way around, making Miller’s claim highly dubious. While Saier acknowledges some may disagree with him, he maintains that the TTSS evolved from the flagellum:

“Regarding the bacterial flagellum and TTSSs, we must consider three (and only three) possibilities. First, the TTSS came first; second, the Fla system came first; or third, both systems evolved from a common precursor. At present, too little information is available to distinguish between these possibilities with certainty. As is often true in evaluating evolutionary arguments, the investigator must rely on logical deduction and intuition. According to my own intuition and the arguments discussed above, I prefer pathway 2. What’s your opinion?” (Milton Saier, “Evolution of bacterial type III protein secretion systems,” Trends in Microbiology, Vol 12 (3) pp. 113-15, March, 2004.)

(B) Behe’s Clear Responses to Evolutionary Appeals to Exaptation:

Secondly, refuting both Judge Jones’s claim that Behe “attempts to exclude the phenomenon of exaptation by definitional fiat” and also Miller’s statement that “Behe’s prediction is that the parts of any irreducibly complex system should have no useful function,” consider these passages from Darwin’s Black Box in which Behe presents the problems of exaptational arguments when discussing the evolution of the cilium:

“Because the cilium is irreducibly complex, no direct gradual route leads to its production. So an evolutionary story for the cilium must envision a circuitous route, perhaps adapting parts that were originally used for other purposes.” (Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, pp. 65-66.)

“For example, suppose you wanted to make a mousetrap. In your garage you might have a piece of wood from an old Popsicle stick (for the platform), a spring from an old wind-up clock, a piece of metal (for the hammer) in the form of a crowbar, a darning needle for the holding bar, and a bottle cap that you fancy to use as a catch. But these pieces couldn’t form a functioning mousetrap without extensive modification, and while the modification was going on, they would be unable to work as a mousetrap. Their previous functions make them ill- suited for virtually any new role as part of a complex system. In the case of the cilium, there are analogous problems. The mutated protein that accidentally stuck to microtubules would block their function as “highways” of transport. A protein that indiscriminately bound microtubules together would disrupt the cell’s shape—just as a building’s shape would be disrupted by an erroneously placed cable that accidentally pulled together girders supporting the building. A linker that strengthened microtubule bundles for structural supports would tend to make them inflexible, unlike the flexible linker nexin. An unregulated motor protein, freshly binding to microtubules, would push apart micrutubules that should be close together. The incipient cilium would not be at the cell surface. If it were not at the cell surface, then internal beating could disrupt the cell; but even if it were at the cell surface, the number of motor proteins would probably not be enough to move the cilium. And even if the cilium moved, an awkward stroke would not necessarily move the cell. And if the cell did move, it would be an unregulated motion using energy and not corresponding to any need of the cell.” (Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, pp. 66-67.)

Previously Behe had also explained evolution does not always necessarily proceed in such a direct route:

“Even if a system is irreducibly complex (and thus cannot have been produced directly), however, one can not definitively rule out the possibility of an indirect, circuitous route. As the complexity of an interacting system increases, though, the likelihood of such an indirect route drops precipitously. And as the number of unexplained, irreducibly complex biological systems increases, our confidence that Darwin’s criterion of failure has been met skyrockets toward the maximum that science allows.” (Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, p. 40.)

Thus contrary to both the Judge’s and Miller’s claims, Behe addresses the possibility that parts can be “co-opted” from other systems and does not shy away from this objection at all. (Indeed, even the basic and introductory pro-ID video entitled “Unlocking the Mystery of Life” deals with the co-option objection.) Behe explains that simply having all of the parts for a system is not enough: one must also have the proper assembly instructions for those parts. Thus, it should be clear that Miller has misrepresented Behe’s argument both by ignoring Behe’s refutation of the co-option theory and by falsely suggesting that Behe holds, “that the parts of any irreducibly complex system should have no useful function [outside of the total irreducibly complex system].”

(C) Miller’s Incorrect Characterization of Irreducible Complexity

To repeat Miller’s assertion, he testified that irreducible complexity is refuted if one sub-system can perform some other function in the cell:

“Dr. Behe’s prediction is that the parts of any irreducibly complex system should have no useful function. Therefore, we ought to be able to take the bacterial flagellum, for example, break its parts down, and discover that none of the parts are good for anything except when we’re all assembled in a flagellum.” (Dr. Kenneth Miller Testimony, Day 1, PM Session, page 16.)

The question becomes, “how is Behe’s argument different from that of Ken Miller?” Behe actually formulates irreducible complexity as a test of building an entire system. IC operates on a collection of parts, not each individual part. Even if a separate function could be found for a sub-system, the latter would not refute the irreducible complexity and the unevolvability of the system as a whole. To repeat Behe’s definition, Behe writes:

“In The Origin of Species Darwin stated:

‘If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.’

A system which meets Darwin’s criterion is one which exhibits irreducible complexity. By irreducible complexity I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning.” (Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, p. 39 (Free Press, 1996).)

Thus, according to Darwin, evolution requires that a system, or its sub-parts, be functional along each small step of their evolution to the final system. Yet one could find a sub-part that could be useful outside of the final system, and yet the total system would still face many points along an “evolutionary pathway” where it could not remain functional along “numerous, successive, slight modifications” that would be necessary for its gradual evolution. (With regards to the flagellum at least 2/3 of the parts are not known to be shared with any other structure therefore might not be even a sub-part of another system at all.)

Thus, Miller mischaracterizes Behe’s argument as one which focuses on the non-functionality of sub-parts, when in fact, Behe’s argument actually focuses on the ability of the entire system to assemble, even if sub-parts can have functions outside of the final system.

A Car Example for Illustration

To understand how Miller’s test fails to accurately apply to Behe’s formulation of irreducible complexity, consider the example of a car engine and a bolt. Car engines use various kinds of bolts, and a bolt could be seen as a small “sub-part” or “sub-system” of a car engine. Under Miller’s logic, if a vital bolt in my car’s engine might also to perform some other function—perhaps as a lugnut—then it follows that my car’s whole engine system is not irreducibly complex. Such an argument is obviously fallacious.

In assessing whether an engine is irreducibly complex, one must focus on the function of the engine itself, not on the possible function of some sub-part that may operate elsewhere. Of course a bolt out of my engine could serve some other purpose in my car. However this observation does not explain how many complex parts such as pistons, cylinders, the camshaft, valves, the crankshaft, sparkplugs, the distributor cap, and wiring came together in the appropriate configuration to make a functional car engine. Even if all of these parts could perform some other function in the car (which is doubtful), how were these parts assembled properly to construct a functional engine? The answer requires intelligent design.

Behe asserts that a system is irreducibly complex if the system stops functioning upon the removal of one part. This is the appropriate test of Darwin’s theory because it asks the question, “Is there a minimal level of complexity which is required for functionality of this system?” Clearly my car’s engine has a core set of parts necessary in order for it to function. The ability of an engine bolt to also serve as a lugnut does not refute the irreducibly complex arrangement of parts necessary to make the final engine-system functional. Behe never suggests that subsystems cannot play some other role in the cell—in fact he suggests the opposite. Rather, Behe simply argues that evolution requires that the total system must be built up in a slight, step-by-step fashion, where each step is functional.

Miller has mischaracterized irreducible complexity, and his test is a straw-test for refuting irreducible complexity. The test for irreducible complexity does not ask “can one small part of the macrosystem be used to do something else?” as Miller claims, but rather asks “can the system as a whole be built in a step-by-step fashion which does not require any ‘non-slight’ modifications to gain the final target function?” Any non-slight modifications of complexity required to go from functional sub-part(s), operating outside-of-the-final system, to the entire final functional system, represent the irreducible complexity of a system.

Even if Miller could find that every part of the flagellum existed somewhere else in bacteria (which he cannot—he only accounts for the basal body, which constitutes about 1/4 of the total flagellar proteins), Miller is no where close to providing a plausible account of the evolution of the flagellum until he has explained how all the flagellar parts might have come together to produce a functional bacterial flagellum. Only then that Miller claim that the flagellum is not irreducibly complex.

Other Authorities Agree with Behe

William Dembski captures the essence of the problem with Miller’s definition and treatment of IC in Dembski’s expert rebuttal in which Dembski writes:

“[F]inding a subsystem of a functional system that performs some other function is hardly an argument for the original system evolving from that other system. One might just as well say that because the motor of a motorcycle can be used as a blender, therefore the [blender] motor evolved into the motorcycle. Perhaps, but not without intelligent design. Indeed, multipart, tightly integrated functional systems almost invariably contain multipart subsystems that serve some different function. At best the TTSS [Type-III Secretory System] represents one possible step in the indirect Darwinian evolution of the bacterial flagellum. But that still wouldn’t constitute a solution to the evolution of the bacterial flagellum. What’s needed is a complete evolutionary path and not merely a possible oasis along the way. To claim otherwise is like saying we can travel by foot from Los Angeles to Tokyo because we’ve discovered the Hawaiian Islands. Evolutionary biology needs to do better than that.” (William A. Dembski, Rebuttal to Reports by Opposing Expert Witnesses, at

http://www.designinference.com/documents/2005.09.Expert_Rebuttal_Dembski.pdf.)

Though Miller has accounted for the origin of only a fraction of the flagellar parts, Scott A. Minnich and Stephen C. Meyer also explain how mere availability of parts is insufficient to explain the evolution of a system:

“[E]ven if all the protein parts were somehow available to make a flagellar motor during the evolution of life, the parts would need to be assembled in the correct temporal sequence similar to the way an automobile is assembled in factory. Yet, to choreograph the assembly of the parts of the flagellar motor, present-day bacteria need an elaborate system of genetic instructions as well as many other protein machines to time the expression of those assembly instructions. Arguably, this system is itself irreducibly complex. In any case, the co-option argument tacitly presupposes the need for the very thing it seeks to explain—a functionally interdependent system of proteins.” (Scott A. Minnich and Stephen C. Meyer, Genetic Analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic

bacteria, p. 8, at https://www.discovery.org/f/389.)

Similarly, philosopher Angus Menuge lays out a number of obstacles which must be overcome by “co-option” or “exaptation” explanations, none of which were addressed by Miller during the trial. Menuge writes:

“For a working flagellum to be built by exaptation, the five following conditions would all have to be met:

“C1: Availability. Among the parts available for recruitment to form the flagellum, there would need to be ones capable of performing the highly specialized tasks of paddle, rotor, and motor, even though all of these items serve some other function or no function.

“C2: Synchronization. The availability of these parts would have to be synchronized so that at some point, either individually or in combination, they are all available at the same time.

“C3: Localization. The selected parts must all be made available at the same ‘construction site,’ perhaps not simultaneously but certainly at the time they are needed.

“C4: Coordination. The parts must be coordinated in just the right way: even if all of the parts of a flagellum are available at the right time, it is clear that the majority of ways of assembling them will be non-functional or irrelevant.

“C5: Interface compatibility. The parts must be mutually compatible, that is, ‘well-matched’ and capable of properly ‘interacting’: even if a paddle, rotor, and motor are put together in the right order, they also need to interface correctly.”

(Angus Menuge, Agents Under Fire: Materialism and the Rationality of Science, pp. 104-105 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2004).)

William Dembski takes a similar approach to that of Menuge. Dembski effectively combines some of Menuge’s criteria in order to develop a means of calculating the probability of constructing an irreducibly complex object. In calculating the probability of a ‘discrete combinatorial object’ one must take into account the probability of originating the parts, the probability of localizing the parts all in once place, and the probability of configuring the parts together:

Table 1. Comparison of Dembski and Menuge’s required explanatory components for any exaptation-based account of evolution (Table based upon the descriptions in William A. Dembski, No Free Lunch: Why Specified Complexity Cannot be Purchased Without Intelligence, p. 291 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002)):

| Dembski’s Factor | Description | Analogue in Menuge’s Criteria |

| Porig | Probability of originating the building blocks for that objects. | C1 |

| Plocal | Probability of locating the building blocks in one place once they are given. | C2, C3 |

| Pconfig | Probability of configuring the building blocks once they are given and in one place. | C4, C5 |

It is clear that Miller has found that the probability for originating about 1/4 of the flagellar proteins might be “1/1” if the TTSS (or perhaps a similar structure) existed prior to the flagellum. However he has not accounted for the origin of the remaining the flagellar proteins, nor has he addressed Plocal or Pconfig in his evolutionary scenario. In light of Menuge’s and Dembski’s criteria, it seems fair to demand answers from Miller to the following questions:

- What function was performed by the paddle, rotor, or motor outside of the flagellum? (At trial, Miller explained the function for the basal body of the flagellum via the TTSS, but left the most complex and vital motorized portions of the flagellum unexplained.)

- How did the parts become synchronized in the flagellum? (At trial, Miller never discussed this.)

- How did the parts become localized within the flagellum at the same construction site? (At trial, Miller never addressed this issue.)

- How did the parts become structurally coordinated so as to interact when assembled to produce the flagellar swimming function? (Again, Miller also never addressed this issue at trial.)

Thus Miller never answered any of these important questions at the trial. Rather, he presented a straw version of testing irreducible complexity whereby he convinced the Judge in a fashion which did not come remotely close to accounting for how the flagellum might have actually evolved.

A Final Analogy: The Arch

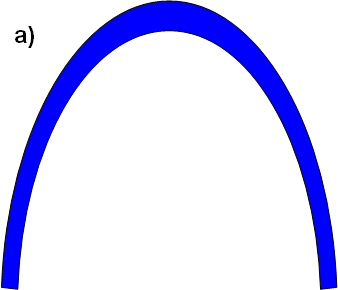

Miller’s treatment of the bacterial flagellum did not refute its irreducibly complexity, as Miller did not address questions about how the final flagellar systems might arise. The existence of other functions for the TTSS does not imply that the flagellar system would not still require large leaps in complexity (or to use Darwin’s words, non-slight modifications) in order to ultimately achieve a functional flagellum. To use a final analogy to show the deficiency of Miller’s explanation, consider an attempt to build an irreducibly complex arch (Figure A):

Figure A: An arch is irreducibly complex: if one removes a piece, the remaining pieces will fall down. (Note: For the purpose of illustration, I am temporarily ignoring the common objection that an irreducibly complex arch might be made using natural erosional processes. I am aware of no appropriate “scaffolding” analogy within the biological realm, but it is not the present purpose of this discussion to rebut that objection.)

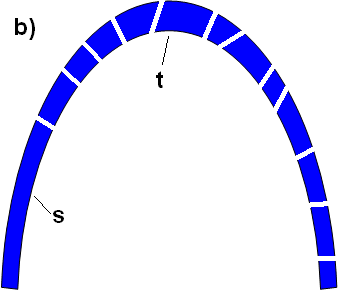

According to Miller, if we can find a function for some sub-piece, then a system is not irreducibly complex. Now, let’s now break this arch into sub-pieces:

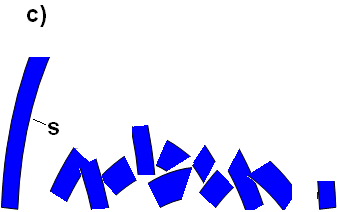

Figure B: Here an arch has been broken up into subpieces. Similarly, Miller has apparently found a flagellar sub-piece (the TTSS) which can perform some other function. The TTSS comprises no more than 1/4 of the total flagellar parts. Similarly, in this arch, there is one large sub-section (labeled “S”) which comprises approximately 1/4 of the total arch. Sub-section “S” can have a function outside of the arch (i.e. here, it can stand on its own). However, this exposes the fallacy of Miller’s test: the ability of sub-section “S” to stand on its own does not therefore dictate that the arch is not irreducibly complex. Thus if one were to removes the top piece (t), the arch crumbles, even if sub-section “S” can still remain standing (Figure C):

Figure C: Even if sub-section “S” can have a function (i.e. stand) on its own outside of the arch, this does not imply that the arch as a whole is not irreducibly complex — capable of being built in a step-by-step manner. Thus, the appropriate test of irreducible complexity asks if the entire system can be built in a step-by-step manner using small, slight-modifications. It is important to note that the system does not become “reducibly complex” simply because one part remains functional outside of the final system.

Correctly Testing Irreducible Complexity

Miller’s test of irreducible complexity is a straw test. The correct test would have stated:

“Dr. Behe’s prediction is that an irreducibly complex system will go through some non-functional stage along any evolutionary pathway. Therefore, we ought to be able to take the bacterial flagellum, for example, remove a part, and discover that the system stops working.”

Miller’s testimony and Judge Jones’s conclusion is based upon a false test of irreducible complexity which focuses on the functionality of one-sub-part, not the functionality of the entire flagellar system.

If Miller could find functions for all flagellar sub-systems outside of the flagellum, he would admittedly be making progress towards an evolutionary explanation by satisfying Angus Menuge’s first criterion of “Availability” (C1). However, as Minnich and Meyer ask:

“[T]he other thirty proteins in the flagellar motor (that are not present in the TTSS) are unique to the motor and are not found in any other living system. From whence, then, were these protein parts co-opted?” (Scott A. Minnich and Stephen C. Meyer, Genetic Analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic

bacteria, p. 8, at http://www.discovery.org/f/389)

Miller has no answer to that question. As it stands, all Miller could provide as evidence for the evolution of the flagellum is the TTSS, and which would account for the availability about 1/4 of Menuge’s first step. Ignoring the fact that the TTSS probably evolved from the flagellum, and not the other way around, if Miller could account for the availability (C1) of all of the parts of the flagellum then Miller would simply have to explain the Synchronization (C2), Localization (C3), Coordination (C4), and Interface compatibility (C5) to account for the evolution of the flagellum; thereby eliminating the need for “non-slight” modifications along its evolutionary pathway.

But Miller did none of this. Despite the inadequacy of Miller’s explanations, Judge Jones decided that Dr. Kenneth Miller’s arguments and inaccurate characterizations of irreducible complexity were correct. This is ruling was made despite the fact that Dr. Scott Minnich, a pro-ID microbiologist and expert on the flagellum, testified extensively at the trial about how his own tests demonstrate the irreducibly complex nature of the flagellum Consider Minnich’s testimony which Jones completely ignored in the Kitzmiller decision:

“A. I work on the bacterial flagellum, understanding the function of the bacterial flagellum for example by exposing cells to mutagenic compounds or agents, and then scoring for cells that have attenuated or lost motility. This is our phenotype. The cells can swim or they can’t. We mutagenize the cells, if we hit a gene that’s involved in function of the flagellum, they can’t swim, which is a scorable phenotype that we use. Reverse engineering is then employed to identify all these genes. We couple this with biochemistry to essentially rebuild the structure and understand what the function of each individual part is. Summary, it is the process more akin to design that propelled biology from a mere descriptive science to an experimental science in terms of employing these techniques.” (Scott Minnich testimony, Day 20, pm session, p. 105.)

Minnich explained how he mutated all of the flagellar genes and found that the flagellum loses function if even one gene is missing. Thus, the flagellum is irreducibly complex with respect to its gene compliment:

“One mutation, one part knock out, it can’t swim. Put that single gene back in we restore motility. Same thing over here. We put, knock out one part, put a good copy of the gene back in, and they can swim. By definition the system is irreducibly complex. We’ve done that with all 35 components of the flagellum, and we get the same effect.” (Scott Minnich Testimony, Day 20, pm session, pp. 107-108.)

Unfortunately Judge Jones chose to ignore this testimony.

Conclusion

Regardless of Judge Jones’ claim, the pro-ID arguments regarding irreducible complexity in the flagellum were never, as Jones said, “refuted.” Miller provided the Judge with a false characterization of irreducible complexity and a straw-method of testing it. Unfortunately, this ruling, which canonized Miller’s misrepresentation of irreducible complexity, will lead the scientific community and the general public to mistakenly assume that the evolutionary origin of the bacterial flagellum can be explained. Incredibly, despite Minnich’s testimony and the presentation of his experimental slides, Judge Jones still held that, “ID . . . has failed to . . . engage in research and testing.” (Kitzmiller ruling, p. 89.)

Had the Judge not also accepted Miller’s fallacious claim that irreducible complexity is not a positive argument for design, but merely a negative argument against evolution, perhaps we might have seen some different findings in this case. Minnich and Meyer make this positive case for the design of the flagellum:

“Molecular machines display a key signature or hallmark of design, namely, irreducible complexity. In all irreducibly complex systems in which the cause of the system is known by experience or observation, intelligent design or engineering played a role the origin of the system. …That we have encountered systems that tax our own capacities as design engineers, justifiably lead us to question whether these systems are the product of undirected, un-purposed, chance and necessity. Indeed, in any other context we would immediately recognize such systems as the product of very intelligent engineering. Although some may argue this is a merely an argument from ignorance, we regard it as an inference to the best explanation, given what we know about the powers of intelligent as opposed to strictly natural or material causes.” (Scott A. Minnich and Stephen C. Meyer, Genetic Analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic

bacteria, p. 8, at http://www.discovery.org/f/389)

In the final analysis, Judge Jones’s ruling on the origin of the flagellum should be disregarded as an example of partisan politics, not as objective or accurate scientific analysis.

I would like to thank Alex Binz, David Klinghoffer, and an un-named biochemist in the University of California system for their help with this post. Any mistakes are my own.

A PDF of this article can be read here.