A Think Tank Treads New Ground

Originally published at InsightRather a few years ago, Bruce Chapman came up with a pair of slightly unorthodox ideas. First he decided that someday he would start a public policy think tank in Seattle — not quite the correct Washington for those who want to be where the action and the gridlock are. And second, he decided that the people in his tank would actually think.

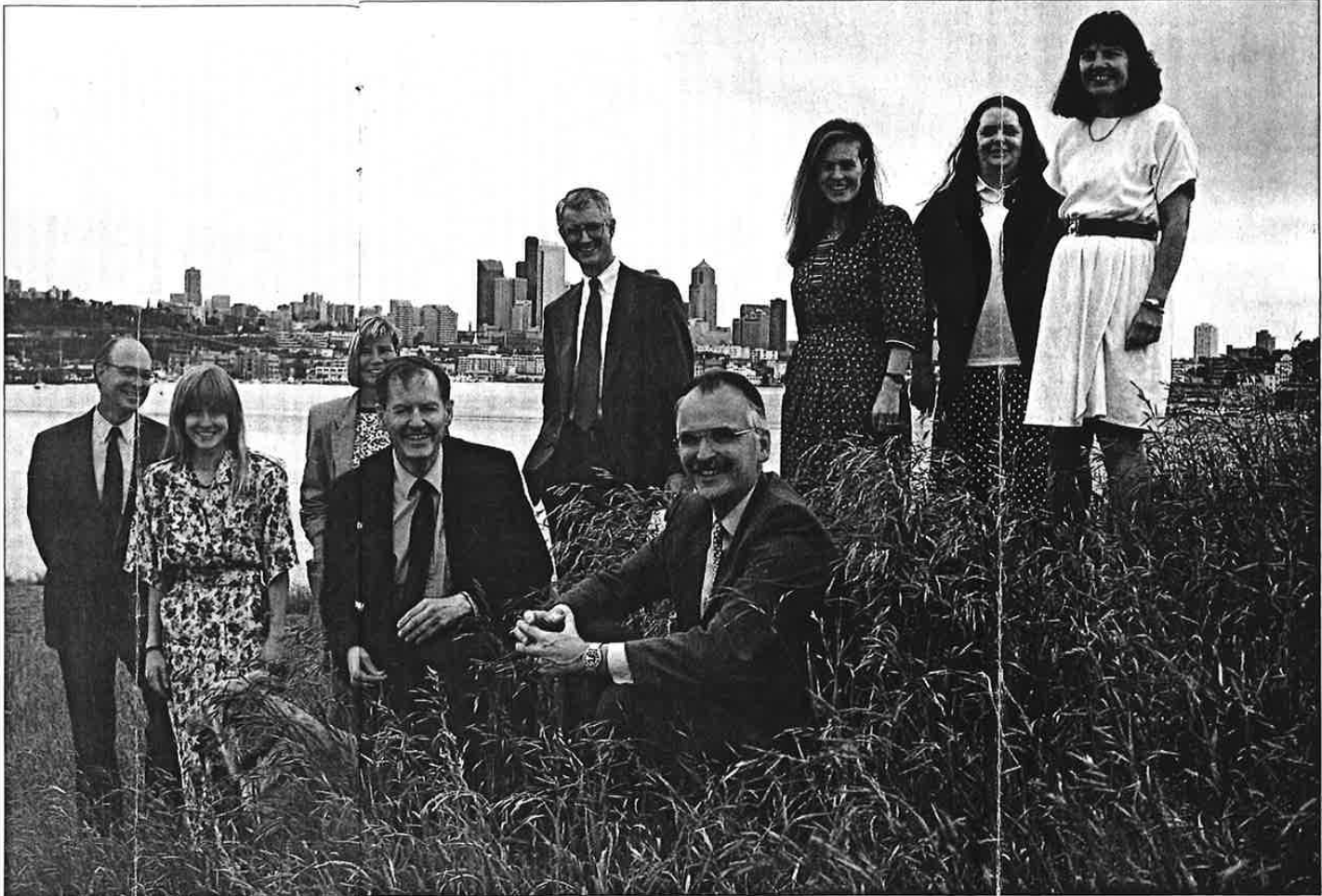

Today, approaching the end of its start-up year, Chapman’s Discovery Institute (named after the British exploring ship, not the cable TV channel) is becoming visible, notably because of senior fellow George Gilder’s most recent book, Life After Television.

Chapman, a former ambassador, Census Bureau director and Reagan White House official, may have founded more than an agile little institute. He may, in fact, have crafted a prime intellectual resource for a new style of assessing the republic’s multitudinous maladies.

“We’re trying,” he says, “to do national and international affairs from a regional perspective, and perspective.”

Discovery is not the only new outfit dealing (or dabbling) in this approach. In reality, states Chapman, “think tanks are going to be all over the country. It’s a sign of sterility in the government and academia.”

But Discovery could well be a prototype.

The history of the species Think Tank, genus Americanus, provides a splendid example of evolution gone entropic. Perhaps the first recognizable modern think tank (as opposed to research institute) was the Rand Corp., based in Santa Monica, Calif. Originally an Air Force adjunct, it was set up to ponder matters of interest to that service (most often, the zestful prosecution of World War III). The breed evolved when Rand became independent and broadened its interests beyond crafting the apocalypse. But the definitive think tank arose only when the late Herman Kahn (himself a Rand alumnus) set up the Hudson Institute in Croton-on-Hudson, N. Y. Judging by the admiration Chapman expresses for Kahn’s approach, Kahn was a virtual role model for him.

“People with ideas need to be brought together,” Chapman says. “One of the things that was so wonderful about Herman Kahn was that he organized a real think tank. You get all these people of various backgrounds and they’re all mixed up together and very creative. The nature of a think tank is that sometimes you don’t know ahead of time [what the results will be]. You have to be willing to come up with a dry hole from time to time.” But few think tanks, sad to relate, perpetuated Kahn’s interdisciplinary (nondisciplinary?) brainstorming approach. And not a few grew sclerotic: ideologically, bureaucratically, spiritually. Compartmentalization–Chapman calls it “credentialing,” or restricting people to their narrow specialties and tasks–set in. And the never-ending hustle for bucks, with its concomitant requirement to be “responsive” to donors (and to the occasional patron who writes out a study’s conclusions along with the check) didn’t help.

“Think tanks suffer from short-term pressures. [Long-term] analysis does not have an economic constituency,” says Chapman. “In the 1930s, you could get any amount of money to look at what tax changes would do to any kind of industry. You can always find money to deal with regulatory problems and hard defense issues. But if you start talking about how to save the American family–programs in these areas have been relatively starved. There’s a lot of big subjects that don’t get studies because there’s no [short-term] economic incentive.”

The result, according to chapman, is that many think tanks, including some of the most prominent, now suffer the very ills they were established to counter and evade. “Some think tanks,” he laments, “even have billable hours. When you have billable hours, people act like lawyers. You get piecework.”

And, he notes with evident dismay, “there’s a lot of intellectual fraud out there, including in the scientific think tanks, so-called. I don’t mean fraud in the legal sense. I mean people creating institutes to pursue a particular point of view. What a think tank does may be of benefit to somebody, some lobbyist can use it, but presumably you don’t start out that way.”

Clearly, Chapman, who had the duty of tracking think tank activity while with the White House, was less than enamored with much of the industry he intended to join. But as the Reagan administration entered its short-timer phase, he pondered returning home to Seattle, where he had once served on the City Council. (He later was the state’s Secretary of State.) Appropriately–but as it turned out, ironically–he persuaded the Hudson Institute, now an Indianapolis-based monolith, to set him up as its one-man Seattle office. He and Hudson also acquired the services of state-of-the-art polymath George Gilder, an old Harvard friend and intellectual coconspirator who remained on the East Coast and novelist/Wall Street Journal—nist Mark Helprin, a Seattle resident.

It didn’t last long.

“I came out in ’90,” says Chapman. “We worked together for about a year and then decided that amicably we would separate. We were raising money here and our local advisory board wanted a say I how the money would be used, while the people in Indianapolis were more oriented toward their own requirements. We left Hudson of our own volition because we wanted more independence.”

Hudson’s president, Les Lenkowsky, agrees that the parting was amicable. He also feels it was desirable and necessary for both sides.

Chapman had talked to him about a Seattle think tank when Lenkowsky was director of research at Smith Richardson, a gran-giving foundation. “When Bruce came to Hudson, before my time,” Lenkowsky says, “he reached agreement with my predecessor that Hudson would try to establish a Seattle office. When I came on board, Bruce was ready to go. I’d reviewed [the situation] even before ’90 and concluded that it would be more sensible to go independent, but Bruce felt he needed the cachet of the Hudson name to get going.

“In the course of working together, Bruce’s interests and needs in Seattle were too often at variance with what we felt were institutional priorities. [Differences] were more administrative than substantive–authority over hiring, salaries, the limits of Bruce’s independence.” Concludes Lenkowsky: “We’re headquartered in Indianapolis. We have a Washington office and plenty of work to do. Seattle added another level of complexity I felt we didn’t need.”

Chapman responds, rather wistfully, that “I’d say that it was a mistake on their part not to see this as an opportunity. I think there was great reluctance there to see us expand too fast.”

Notes Helprin succinctly: “Bruce was raising so much money out here that it was becoming an independent entity.”

After the formal break this past October, Chapman began engineering the think tank of his intellectual fantasies. For reasons both philosophical and financial (the current annual budget is around $500,000), he decided to forgo, at least temporarily, a large paid staff. “We would have to grow much bigger to start having most of our people salaried. [For now] I would rather have people who do something else for a living and integrate this.”

Integration proceeded. Gilder and Helprin stayed on; Chapman quickly recruited nearly a dozen other fellows around the country: academics, journalists, lawyers, scientists. Gilder calls it a “distributive think tank,” made possible by modern telecommunications. (One of the institute’s projects is a traveling series of seminars on the possibilities of the new technologies.)

But wherever based, most of the new members have two things in common. First, as senior fellow Patricia Lines puts it: “links to the Pacific Northwest.” Lines, who is working on school choice issues, teaches at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., but summers here in Seattle. Several other fellows are similarly bicoastal.

Second, many of the fellows possess multiple expertise. Gilder has long been acknowledged as a consummate generalist. Helprin, a best-selling novelist, moves as easily in the worlds of military affairs and international relations as in those of fiction and aesthetics. (At an early 1991 meeting, and in his Journal columns, he accurately predicted the course of the Persian Gulf war.) Another senior fellow, David Hancocks, an architect/naturalist by osmosis, runs the Arizona-Sonora desert Museum in Tucson and writes books with titles such as Animals and Architecture. Roberta Katz, a Seattle attorney, also holds a doctorate in cultural anthropology and is combining both disciplines for a book on the demoralization of the legal profession.

Says Chapman: “If we salaried her, she would suddenly have a professional interest in the subject, rather than being a professional with a public policy outlet.”

Chapman himself is working on another kind of demoralization: of American political life and “how we got into this box. People are trying to break up the problem. How do we improve campaign reporting? What do we do about leaks? What about conflict of interest? Everybody has a series of specific programs. What they don’t have is anything that links all those together, or even a common philosophy.”

According to Chapman, the fundamental problem is that “we have demeaned the people in the process. The Aristotelian question of how do you get the virtuous person to serve is missed. The question today is how do we make the people who serve more virtuous. “That,” he concludes, ” is for the criminal justice system. Not politics.” And though he declines to discuss his ideas more specifically (the stuff is still fermenting), he predicts that the final product will include “a series of essentially conservative reforms to get good people to serve.”

For the moment, though, Greater Seattle may have more to teach America than Aristotle. Senior fellow John Hamer, a former Seattle newspaper editor, works on a project titled, perhaps a bit hyper cosmically, “International Seattle: The Making of a Global Community.” The effort, he says, “is to come up with a set of recommendations on how metropolitan Seattle can be more competitive internationally. A lot of people would say we already are, with Boeing and Microsoft [and the second busiest port in the country]. But there are things we ought to be doing more of and better.”

Yet the project transcends mere boosterism. It requires looking at the region as it relates to the rest of the country, nearby Canada, the Pacific Rim and Europe. It entails studying other successful trading cities; Hamer has visited Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Stuttgart, Germany, among other places. The narrow focus (and funding) may be local, but the conclusions could well have national implications for competitiveness and growth.

“It’s kind of our hope” that they do, says Hamer. “We’re not suffering from any grandiose delusions that we can tell the rest of the country what to do. But I think we may be able to come up with approaches and priorities that other cities can look at.”

If so, and if the regional approach to national problems yields dividends in other areas Discovery is studying–homelessness, education, and the family–it may tie in well with a political phenomenon last seen circa 1912, but now perhaps renascent. “The states and cities,” says Gilder, “have always been laboratories for democracy.” During the Progressive Era, locales as diverse as Wisconsin, Ohio and Colorado pioneered modern reforms while the banks-of-the-Potomac types (there bing no defining Beltway yet) blessed the country with, among other things, the income tax, the career civil service and the Federal Trade Commission. After a Washington-dominated hiatus of nearly a century, the locus of innovation may be decentralizing again.

But with two vital changes. First, suggests Hamer, “metropolitan regions are even more of a laboratory than states [or cities]. We’re studying more than Seattle. Metropolitan regional economies are becoming major players in global markets.”

Second, believes Gilder, the revolution in telecommunications and computing–the “telecoms,” as he calls it–will make it ever easier for regions to operate without central control or strings-attached largess, indeed, to sometimes bypass Washington, D.C., entirely (which was, after all, why the Beltway was built).

But whatever the implications for public policy, Gilder asserts, “this is an exciting venture. Bruce is really recapturing the inspiration of Herman Kahn.”

Says Chapman, more modestly: “We want to grow into what a think tank should be.”