How Evolution Uses Natural Selection to Build Organisms

Synopsis: How Natural Selection WorksWhat is natural selection and how does evolution use it to build new organisms? The fundamental difficulty for any undirected process of evolution is being able to see into the future and determine what functions that organism will need to survive. An unguided process like natural selection is incapable of doing that. What natural selection and other undirected natural mechanisms cannot achieve however, an intelligent agent can.

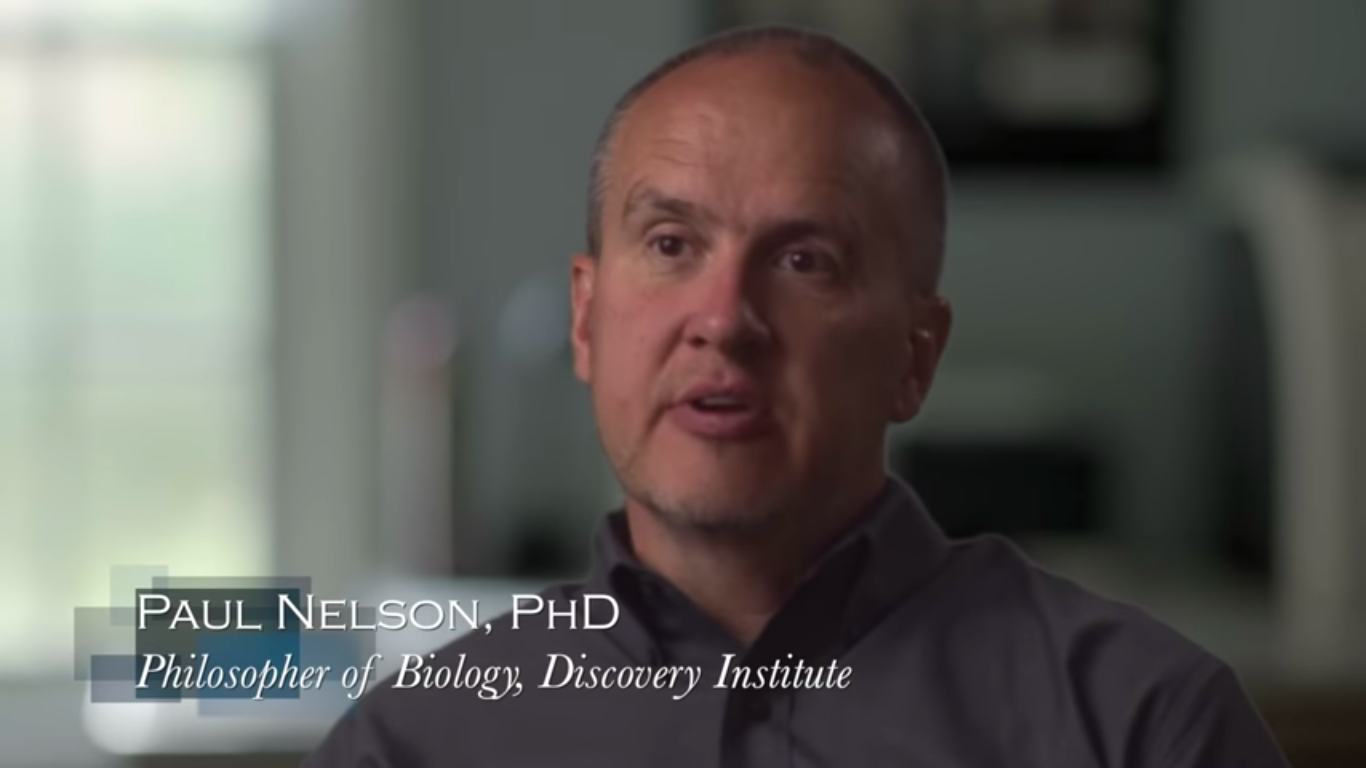

Philosopher of Biology Paul Nelson describes the amazing process by which the worm C. elegans is constructed and how it points toward intelligent design.

Primer: Mutations in a Nutshell

From Intelligent Design & Evolution Awareness Center

Evolutionary theory asserts that random mutations (changes in the DNA code), followed by natural selection, can result in complicated and functional protein structures. But mutations are almost always harmful. As Nobel Prize winner H.J. Muller concedes, “[i]t is entirely in line with the accidental nature of natural mutations that … the vast majority of them (are) detrimental to the organism in its job of surviving and reproducing, just as changes accidentally introduced into any artificial mechanism are predominantly harmful to its useful operation.” French evolutionist Pierre-Paul Grasse noted, “[n]o matter how numerous they may be, mutations do not produce any kind of evolution.” Similarly, leading biologist Lynn Margulis (who opposes intelligent design) argues that “new mutations don’t create new species; they create offspring that are impaired” and writes that “Mutations, in summary, tend to induce sickness, death, or deficiencies. No evidence in the vast literature of heredity changes shows unambiguous evidence that random mutation itself, even with geographical isolation of populations, leads to speciation.”

CodonDNA consists of a complex code formed of four “letters” that are arranged into three letter “words.” Each word codes for a subunit of a protein, an amino acid. The proteins are analogous to complex machines, in that they have moving parts that repetitively perform a task. Several classes of mutations are shown above, but even in this simple illustration it is obvious that random changes in code do not increase the information content, making it unlikely that DNA mutations are responsible for the complex specificity of life.

One oft-cited “beneficial” mutation is bacterial antibiotic resistance. Yet antibiotic resistance does not introduce new information into the genome. This is microevolution because it involves only minor change “within a species” and does not add information. Antibiotic resistance is not macroevolution and does not explain how new biological structures arise; it never results in one bacterial species becoming another. Interestingly, antibiotic resistant bacteria face a net “fitness cost” and are weakened by the very mutation that made them drug-resistant.

The Deniable Darwin

CHARLES DARWIN presented On the Origin of Species to a disbelieving world in 1859–three years after Clerk Maxwell had published “On Faraday’s Lines of Force,” the first of his papers on the electromagnetic field. Maxwell’s theory has by a process of absorption become part of quantum field theory, and so a part of the great canonical structure created by mathematical physics.

By contrast, the final triumph of Darwinian theory, although vividly imagined by biologists, remains, along with world peace and Esperanto, on the eschatological horizon of contemporary thought.

“It is just a matter of time,” one biologist wrote recently, reposing his faith in a receding hereafter, “before this fruitful concept comes to be accepted by the public as wholeheartedly as it has accepted the spherical earth and the sun-centered solar system.” Time, however, is what evolutionary biologists have long had, and if general acceptance has not come by now, it is hard to know when it ever will.

IN ITS most familiar, textbook form, Darwin’s theory subordinates itself to a haunting and fantastic image, one in which life on earth is represented as a tree. So graphic has this image become that some biologists have persuaded themselves they can see the flowering tree standing on a dusty plain, the mammalian twig obliterating itself by anastomosis into a reptilian branch and so backward to the amphibia and then the fish, the sturdy chordate line–our line, cosa nostra–moving by slithering stages into the still more primitive trunk of life and so downward to the single irresistible cell that from within its folded chromosomes foretold the living future.

This is nonsense, of course. That densely reticulated tree, with its lavish foliage, is an intellectual construct, one expressing the hypothesis of descent with modification.

Evolution is a process, one stretching over four billion years. It has not been observed. The past has gone to where the past inevitably goes. The future has not arrived. The present reveals only the detritus of time and chance: the fossil record, and the comparative anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of different organisms and creatures. Like every other scientific theory, the theory of evolution lies at the end of an inferential trail.

The facts in favor of evolution are often held to be incontrovertible; prominent biologists shake their heads at the obduracy of those who would dispute them. Those facts, however, have been rather less forthcoming than evolutionary biologists might have hoped. If life progressed by an accumulation of small changes, as they say it has, the fossil record should reflect its flow, the dead stacked up in barely separated strata. But for well over 150 years, the dead have been remarkably diffident about confirming Darwin’s theory. Their bones lie suspended in the sands of time-theromorphs and therapsids and things that must have gibbered and then squeaked; but there are gaps in the graveyard, places where there should be intermediate forms but where there is nothing whatsoever instead.

Before the Cambrian era, a brief 600 million years ago, very little is inscribed in the fossil record; but then, signaled by what I imagine as a spectral puff of smoke and a deafening ta-da!, an astonishing number of novel biological structures come into creation, and they come into creation at once.

Thereafter, the major transitional sequences are incomplete. Important inferences begin auspiciously, but then trail off, the ancestral connection between Eusthenopteron and Ichthyostega, for example–the great hinge between the fish and the amphibia–turning on the interpretation of small grooves within Eusthenopteron’s intercalary bones. Most species enter the evolutionary order fully formed and then depart unchanged. Where there should be evolution, there is stasis instead–the term is used by the paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge in developing their theory of “punctuated equilibria”–with the fire alarms of change going off suddenly during a long night in which nothing happens.