James’s Faith

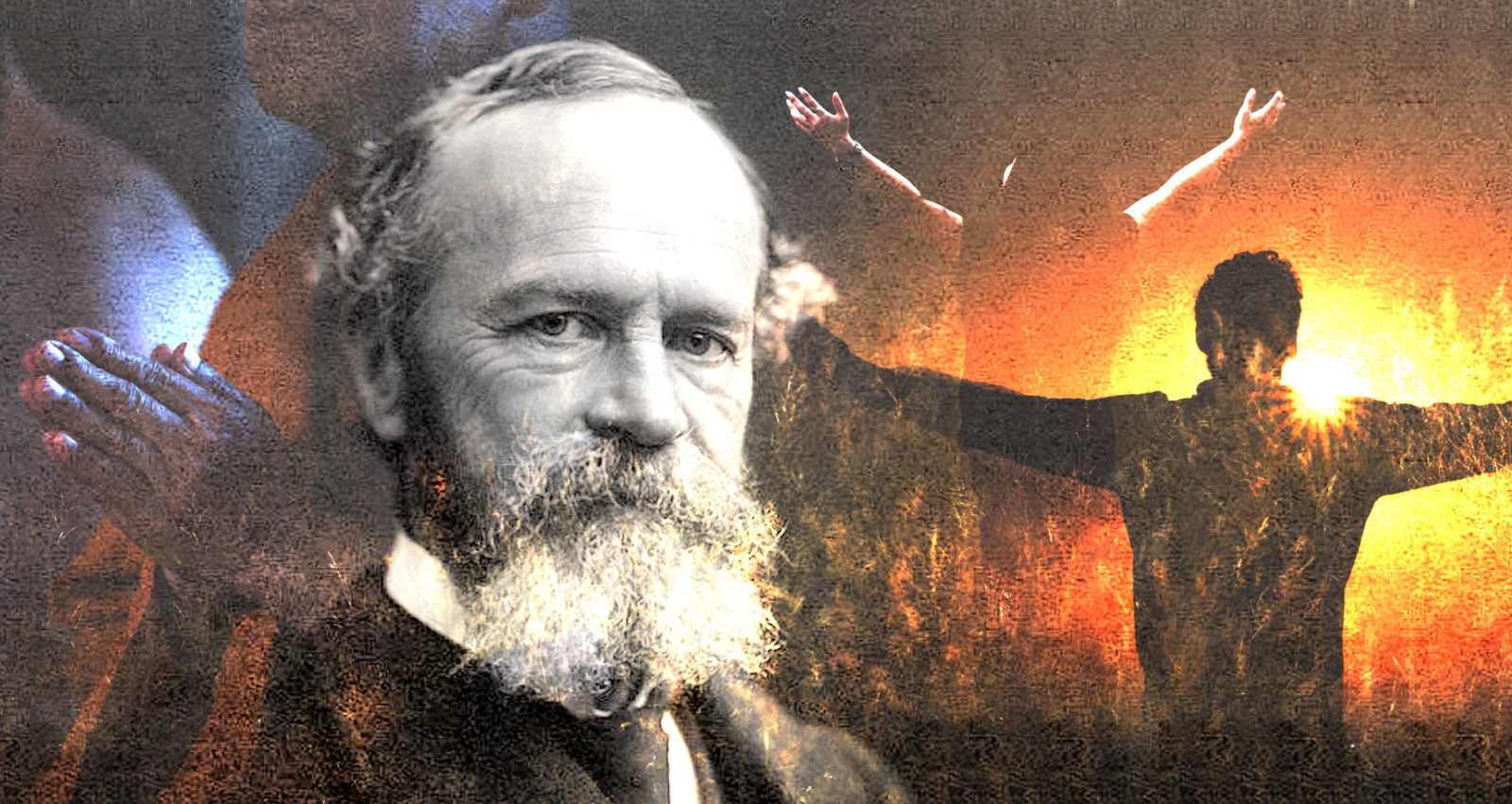

The pragmatist who understood the value of religion The Weekly StandardWilliam James

In the Maelstrom of American Modernism

by Robert D. Richardson

Houghton Mifflin, 622 pp., $30

The series of New Atheist tracts that have shot up the bestseller list seem like distress flares launched from the deck of a foundering ship at sea. Surely the enthusiastic reception bestowed on these books, led by Christopher Hitchens’s God Is Not Great and Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion, signals that something has gone wrong in an unprecedented way with our supposedly religious national culture.

Or has it? A comforting observation to be drawn from Robert Richardson’s fine biography of the philosopher and psychologist William James is that America went through a similar crisis more than a century ago, pitting atheism against theism. That we emerged intact then may have been thanks partly to insights offered by James. Those insights remain fresh, both in their expression–he was a fantastic writer (as is Richardson)–and in their content, which has lost little of its relevance. The only fault in Richardson’s William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism is that the biographer doesn’t draw out the contemporary relevance, the echoes of our times, in his compelling narration of the life of his subject.

William James (1842-1910) grew up, like his brother the novelist Henry James, in a household saturated with God-talk. Their father, Henry James Sr., was permitted by family money to spend his time writing a succession of cryptic, mystical theological texts. Yet as a young man, William James was less interested in religious enthusiasm than in Darwinian evolution. His mentor at Harvard was the anti-Darwinian zoologist Louis Agassiz, whose views James ultimately rejected.

James was a born teacher, going on to teach psychology and philosophy to Harvard students for 35 years. He also had a knack for counseling, possessing as he did a tremendous–if erratic–sympathy for others. James was devoted to his wife Alice, but Richardson describes him as a “philanderer,” if not an overtly sexual one. He indulged in “a mad crush on every other woman he met,” which he didn’t bother to hide from an increasingly wounded Alice.

Despite bouts of hypochondriac worries and genuine ill health, he was massively productive. James’s groundbreaking explanations of how the mind works–as in his Principles of Psychology (1890)–seem less provocative now than they once did. On the other hand, his less academic contributions to what we may call the field of self-help still captivate. Some of his views sound like a less flaky version of Rhonda Byrne’s The Secret. This phenomenally popular, Oprah-endorsed film-and-book combo purports to explain how, by imagining what you want (wealth, health, anything), you can have it. James thought that there are, indeed, areas where believing in something can make it so. He gave as an example that, if you want to win a woman’s heart, it improves your chances to think and act as if she already loves you.

He might have been recalling his own affection, at age 28, for a gravely ill young woman named Minnie Temple. It was her death in 1870 that initiated James’s engagement with religion. A month after, he was overtaken by a terrifying vision. While fully awake, he suddenly saw in his mind an epileptic patient from an asylum he had visited, “a black-haired youth with greenish skin, entirely idiotic,” who “sat there like a sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes and looking absolutely inhuman.” Reeling at the thought that such a condition could befall himself, James took refuge in Biblical verses.

The defense of religion became a salient theme in his work. Why the continued attraction to it? Richardson smartly observes that much of William James’s best intellectual energy was poured into defying academic and elite assumptions: “James moved toward a major idea by starting out in opposition or resistance to received ideas.” One such idea was Darwinism. James the instinctive contrarian lived through Darwinian evolution’s earliest acceptance, which he often noted with approval even as he perceived its challenge to religion. It led to a view–“widespread at the present,” he said in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902)–that religion was only a relic surviving from the primitive past. In opposing this “survival theory,” James saw that “the current of thought in academic circles runs against me.” He relished that fact.

In his philosophic work Pragmatism (1907), James observed that Darwin had displaced “the argument from design,” with the result that “theism has lost that foothold.” While rejecting conventional theism for himself, he also chastised the overly refined religious believer who worships a deity that never impacts the physical world. Such a believer “surrenders . . . too easily to naturalism” so that “practical religion seems to me to evaporate.” Why would a religious person concede so much ground? James pointed out that certain ideas are embraced by an uncritical public simply because of their “prestige.”

He himself felt “like a man who must set his back against an open door quickly if he does not wish to see it closed and locked.” Shrewdly, he noted that, in keeping a door open for faith, he had more credibility because he was not orthodox–indeed, he was irritated by orthodox Christianity–but rather an outside observer.

We can imagine his response to our New Atheists. In dealing with secularists in his own day, he appealed to experience, reason, and pragmatism. James argued that subjective experience has been undervalued as a source of enlightenment. In his essay “The Will to Believe,” he explained that personal experience which would confirm religion’s truth “might be forever withheld from us unless we met the [religious] hypothesis half-way.” In other words, those who reject religion, for fear of being duped, have sealed themselves off from ever knowing whether they are wrong:

I, therefore, for one, cannot see my way to accepting the agnostic rules for truth-seeking, or willfully agree to keep my willing nature out of the game. I cannot do so for this plain reason, that a rule of thinking which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth if those kinds of truths were really there, would be an irrational rule.

Citing God’s instruction to the -Israelite leader Joshua, “Be strong and of a good courage” (Joshua 1:6), James argued that it is more reasonable to act from the hope that religion is true than it is to spurn faith out of the worry that it might be false. The religious act could even produce its own confirmation. Action creates reality. This is different from Pascal’s wager. It’s more like a vote for faith, which can generate the reality it endorses.

The idea wasn’t original with him. It had already been crystallized by the book of Exodus (24:7), which records the declaration of the Jews in receiving the Ten Commandments: “Everything that the Lord has said, we will do and [then] we will understand.” They would comply now with the commandments in the expectation that later, as a result of casting their vote for God, they would understand why He commands what He does. That illumination would confirm that God is a reality. To believe, and know that you’re right to believe, you must first act.

That his religious psychology was anticipated in the Bible would not surprise William James. He appreciated Scripture as a “guide to life,” the practical effects of whose guidance can be gauged. According to his philosophy of pragmatism, this is the preferred way to evaluate any truth claim. Pragmatism, he wrote, has “no materialistic bias as ordinary empiricism labors under” and judges theological ideas by the twofold criteria of whether they have “value for concrete life” and whether they mesh with “other truths that also have to be acknowledged.”

Religion should make any individual believer better than he would be without it. It should not, rightly understood, violate science. It should provide a framework for diagnosing the ills of a culture, and for prescribing measures for the amelioration of social and political problems. If a biblical worldview does a better job of these than the secular alternative, that makes religion “true.”

Yet James, that beguiling man, advocated a sense of humor about the fact that, despite our faith, notwithstanding our arguments for belief, we might have it all wrong. Then again, perhaps it’s the New Atheists who have shut their ears to truth. Not that they would be likely to admit the possibility.